Sumru Krody on Turkish Kilims from the Megalli Collection

On January 6, 2018, Sumru Krody,

Senior Eastern Hemisphere Curator, at The Textile Museum, here in Washington, DC, gave a Rug and Textile Appreciation Morning Program on “Turkish Kilims in the Megalli Collection.” This program anticipated an upcoming TM exhibition on this material.

A Nomad’s Art: Kilims of Anatolia

Woven by women to adorn tents and camel caravans, kilims are enduring records of life in Turkey’s nomadic communities, as well as stunning examples of abstract art. This exhibition marks the public debut of treasures from the museum’s Murad Megalli Collection of Anatolian Kilims, dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Howe: Sumru, most readers will know, is a long-time curator at The Textile Museum and has been involved in and/or produced a large number of exhibitions and publications, which I will not enumerate here.

The Myers Room was full.

*

Sumru began:

“Kilim” is a general name, given in Anatolia and its surrounding areas in West Asia, to a group of sturdy, utilitarian textiles, woven in slit tapestry-weave technique.

These works of art are multifaceted objects and obviously played an important role in the artistic history of Anatolia.

The highly-developed designs and the fine execution, seen on the surviving eighteenth- and nineteenth-century kilims I will share with you during the next 45-minutes or so, suggest that the Anatolian kilim tradition had been well-established by the time the seventeenth century came to a close.

Note: About the images in this post. Initially, in each case, you will see an image of a given piece, like the one below. Please click on the initial images and you will get a larger one. There is also a third image, one turned 90 degrees to the right that lets you see this piece most closely

2

*

*

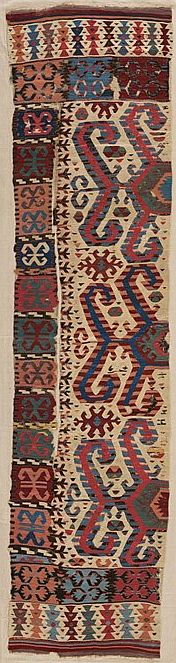

Kilim, Central Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.59, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 417 X 95 cm (164 X 37 inches)

Turned image of 2:

*

Sumru:

Formed with wool fibers and tapestry weave technique, Anatolian kilims represent a distinct weaving tradition, while conforming to the mechanics of tapestry weaving practiced in many parts of the world.

3a

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning, weft-faced plain weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.6, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 308 X 75 cm (121 X 29.5 inches)

*

Sumru:

Many consider the kilims of Anatolia to be great contemplative and minimalist works of art.

3b

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, c. 1800, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.44, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 313 X 67 cm (123 X 26 inches)

*

*

4

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, very small amount of vertical color change. The Textile Museum 2013.2.73, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 394 X 84 cm (155 X 33 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

They were created by women who had a great eye for design, and an awesome sense of color.

They are prized for the harmony and purity of their color, the integrity of their powerful overall design, their masterfully controlled tapestry weave structure, and their fine texture.

5

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning,\supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.90, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 367 X 88.5 cm (144.5 X 34.5 inches)

*

Sumru:

The visually stunning and colorful Anatolian kilims communicate the aesthetic choices of the nomadic and village women who created them.

Yet, while invested with such artistry, Anatolian kilims first and foremost were utilitarian objects

initially employed by nomadic families for a host of uses, primarily but not exclusively for covering household items and furnishing the interior sides of tents.

6

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.72, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 343 X 158 cm (135 X 62 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

Since 2015, I have been documenting a private collection of 96 Anatolian flatweaves donated to The Textile Museum .

I have been engaged in analytical study of these textiles in order to contribute to our understanding of the Anatolian kilim weaving tradition.

91 of these 96 flatweaves are kilims,

43 are attributed to Central and South Anatolia,

7a

*

*

Kilim, Northwestern Anatolia, 18th century to early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.81, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 147 X 79 cm (57.5 X 31 inches)

*

*

7b

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, c. 1800, wool, slit tapestry weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.68, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 401 X 86 cm (157.5 X 33.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

38 to western and northwestern Anatolia,

*

8

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly east-central, mid-19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, eccentric weft, lazy lines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.19, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 444.5 X 69 cm (175 X 27 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

and 15 to eastern Anatolia.

9

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft, weft-faced plain weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.31,The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 137 X 387 cm (54 X 152.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

What I am about to present to you today is where I am in my investigation.

This being still an on-going research, there is room for improvement, and I appreciate hearing your questions and comments.

10

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, c. 1800, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.14, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 292 X 160 cm (115 X 63 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

I started, like any research project should, with questions that, I hope, will help me to better understand these textiles and their creators,

and answer the fundamental question of:

11

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, cotton, slit tapestry weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.7, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 181.5 X 138 cm (71.5 X 54 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

What is there to see when you look at a work of art, such as an Anatolian kilim?

I also wanted to know:

- What is an Anatolian kilim?

- Who were the artists who created these weavings?

- How did their lifestyle affect their artistic creation?

- How do artistic form and function come together in Anatolian kilim?

- How do materials influence what an artist makes in the context of Anatolian kilims?

- How does this artistic tradition change over time?

- How does a kilim’s design affect the way it is seen?

12

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly west-central, early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.30, The Megalli Collections.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 428.5 X 67 cm (168.5 X 26 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

But the most elusive questions and the most important, at least for me, are:

- What did Anatolian nomads value in the kilims?

- What criteria did they use to judge these items?

- Were they the same as ours? Or different? And, if different, how different?

*

13

*

*

Sumru:

Kilim, a type of textile, is often referred to as flatweave in the western literature because it does not have any pile or tufts, as carpets do.

The tapestry-weave technique is very old—archaeological examples go back well over two millennia—and very geographically widespread.

Textiles with tapestry weave are created in traditional Islamic carpet-weaving societies from Morocco to Central Asia, and more broadly, from the pre-Columbian Americas to ancient China, as well as to the European Medieval and Baroque tapestries.

*

14

*

*

Sumru:

In slit-tapestry weave technique, as used in the Anatolian kilims, the design is created by colored horizontal weft yarns, interlaced in an over and under sequence, through the vertical warp yarns and completely obscure them.

Like any tapestry-woven textile, Anatolian kilims have weft-faced plain weave structure, but the real essence of Anatolian kilim is its slit-tapestry structure. The design is built up of small areas of solid color, each of which is woven with its individual weft yarn, and that between two such adjacent areas the respective weft yarns never interlock or intermingle.

The different colored weft yarns turn back, using adjacent warp yarns. The result is a vertical slit. In this manner, the artistic expression of the kilim and its technique are inextricably bound together.

*

15

*

Sumru:

Anatolia was a crucial transitional point between the weaving regions of Europe, Asia, and Egypt. Its history is one of ancient, continuous interactions between the culturally diverse people.

16

*

*

Sumru:

Weavers of kilims were descendants of Turkmen nomads and their settled kin.

Turkmen—ethnic Turkish nomads—began to arrive into Anatolia in about the 10th century, adding further diversity to already ethnically diverse area.

The lands they passed through on their way from further east, via Central Asia to Anatolia, were occupied by two different religions, Islam and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, and two distinct cultures, Persian and Byzantine/Greek.

17

*

*

Sumru:

Nomadism, is a style of life, in which groups of people, mostly close family members, move from one region to another to exploit the resources, like grass.

Anatolian nomads’ living and economic units were predominantly groups of families (kabile) or of extended families (aile).

They were generally herders and depend on their large flocks for their livelihood. Some nomadic groups, such as those in Anatolia, are pastoral nomads, or semi-nomadic, meaning they move between two pastures, one for winter and one for summer.

Nomadism is a lifestyle and separate from tribalism

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

18

*

*

Sumru:

Two major, but distinct, activities dominated the life of the Turkmen nomads:

1.Migration to winter pasture, called kisla, and to summer pasture, called yayla.

Kisla = low elevation, in the valleys, that are warmer in the winter

Yayla= higher elevation, on the mountains, that are cooler in the summer

19

*

*

2. Pastoral life or life in pasture

There are very few if any nomads left in the Anatolia today. If there is any migration today, so-called nomads live in brick and mortal houses by the coast during winter and move up to mountains in the summer, pitching tents in yayla.

*

20

*

*

Sumru:

The last remaining nomads were, in the mid-20th century, congregating in the Taurus Mountains, which parallel the north Mediterranean coast of Anatolia.

*

21

*

*

Sumru:

During the twice-yearly movements, camels carried family’s belongings including the tent, while the family, except the youngest ones, walked alongside the camels.

During the migration, women could display their weaving skills, through the display of kilims thrown over the camel loads, to everyone they encountered on the road.

22

*

*

Sumru:

When they arrived at the destination, the most pressing issue was to establish a shelter/home for the family.

23

*

*

Sumru:

Once settled in yayla or kisla, nomadic women could have time to devote themselves to weaving.

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

24

*

*

Sumru:

Although utilitarian, the textiles were carefully woven and intricately decorated.

We can speculate that the reason for this care was that textiles had artistic, social, and religious importance, for the nomads, in addition to their pure functionality.

25

*

Photography by Josephine Powell, KOC Foundation Archives

Sumru:

Unfortunately for us, we are so removed from these societies, today, that it is hard for us to perceive the specifics of these aspects, and especially not through examining these objects.

26

*

*

Sumru:

We do not know how a nomad family organized their tent, in the 17th or 18th or even early 19th century. We are inferring the way they lived then, by analogy, with how their decedents were living in the mid 20th century.

We are grateful the research done by Harald Bohmer, Josephine Powell and many others in 1970s, 80s and even some in 90s to preserve the 20th century way of nomad life.

But, we should always remember that we do not have direct access to the earlier kilim weavers. We are gathering our information among the great great grandchildren of nomads who wove the kilims in our collections, and we are relying on the notion that they have been living in very conservative, little changing environment, which is not true.

27

*

*

Sumru:

Textiles were prominently displayed when the family reached the pastureland and set up tent.

Each tent formed a single open space with a wooden post in the middle.

The large transportation bags, that carried family’s belongings during the migration, were turned into storage bags and placed in various parts of the tent.

And were covered with long kilims, that were previously used as covers during migration. Occasionally, these long kilims served as wall hangings.

In short, by rearranging kilims and other textiles, women defined the single tent space for different functions.

28

*

*

Sumru:

The practice of using textiles, to delineate living spaces, continued when nomads permanently settled in villages.

Once nomadic, now-settled women continued weaving their kilims and bags for couple of generations, though storage bags and other textiles gradually disappeared from their weaving repertoires. Only the kilim weaving appeared to be continued.

On reason for that might have been that kilims were flat rectangular textiles that could serve multiple functions as wall hangings, bedding covers, and even floor covers. And in 20th century, they brought income to the family through their sales.

29

*

*

Sumru:

Kilims also were used to honor the deceased. When a member of the family died, the body would be wrapped in a kilim and carried to the gravesite.

The kilim was not buried; however. It would be washed and presented to the mosque, at mevlut ceremonies, gatherings to honor the deceased and held forty days after their burial.

30

*

*

Kilim, Central or Western Anatolia, c.1800, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.94, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 381.5 X 70 cm (150 X 27.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

The creation of Anatolian kilim was, from start to finish, the work of a single weaver or family group.

The same group of people completed the full production cycle of creation.

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

31

*

*

Sumru:

They sheared the sheep,

32

*

*

Sumru:

chose the wool,

33

*

*

Sumru:

turned loose fibers to yarn

34

*

*

Sumru:

dyed the yarns, set up the loom, and, as the weavers say “dressed the loom.”

35

*

*

Sumru:

Then, they decided on design and wove the textiles.

36

*

*

Sumru:

The weavers had total control over the selection of their raw material.

The weavers’ involvement from the beginning in choosing, cleaning, and combing the wool to make it ready for spinning was an important factor in achieving the high weaving quality seen in the kilims.

Kilim designs that are clear and precise, and colors that are luminous and bright, are almost always made with high quality wool.

37

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, c. 1800, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.8, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 388 X 77.5 cm (152.5 X 30.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

The total involvement and control of raw material and preparation of the yarn did not translate to total freedom of design, however. Anatolian women designed their kilims, but they chose from a rigid traditional design repertoire.

The young weaver was expected to use the motifs and design layouts that were accepted by her community as theirs—their artistic tradition.

38 upper

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.74, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 445 X 94 cm (175 X 37 inches)

*

*

38 lower

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.71,The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 364 X 90 cm (143 X 35.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 38 upper and lower:

Only after a weaver had assimilated and internalized these motifs, and the mechanics of weaving them to such a degree that she became a skilled master, did she become comfortable with introducing variations and minor innovations to the traditional design.

Even the skilled and experienced weaver could do so only if she maintained, and did not displace, the accepted form.

39

*

*

Kilim (detail) western Anatolia, Aydin, first half of the 19th century, wool, slit-tapestry weave, The Textile Museum, 2013.2.9 The Megalli Collection.

*

*

Sumru:

So an Anatolian kilim could not be considered the overt self-expression of one individual, but rather an expression of the collective, the tradition.

Conversely, each kilim was different from the others. Even in this restricted environment, the individualism was manifested in minor details, as long as the weaver followed the expected traditional forms.

40 upper

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.32, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 357 X 115.5 cm (140.5 X 45.5 inches)

*

*

40 middle

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly west-central, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.48, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 312.4 X 110.5 (123 X 43.5 inches)

*

*

40 lower

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly west-central, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.64, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 371 X 76 cm (146 X 30 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 40 upper, middle and lower:

Many factors influence the uniqueness of each kilim. The individual personality of weaver, her nature, her understanding of colors, ability to design, weaving skills, and different levels of expertise/experience in weaving, all play a role, as did external factors.

Changes in the conditions of the family group—the influx of new families into the group and marriage among individuals from different nomadic groups—brought in new ideas. Chance exposure of weavers to new motifs, during migration, or occasional visits to a mosque, allowed new motifs to be appreciated and memorized.

41

*

*

Sumru:

The mode of learning in kilim weaving was memory, rather than the invention or creation.

This involved memorizing a small set of motifs/design elements, and the mechanics of weaving this same set of motifs.

In other words, it appears that young weavers mastered the weaving technique, and the motifs that go with it, simultaneously. The learning process was both visual and tactile memorization.

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

42

*

*

Sumru:

Nowadays they use cartoons.

43 upper*

*

Kilim, central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, The Textile

Museum 2013.2.27, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 310 X 93 cm (122 X 36.5 inches)

*

*

43 lower

*

*

Kilim, central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, The Textile

Museum 2013.2.35, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 293 X 137.5 cm (115 X 54 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 43 upper and lower:

Through close examination of the kilims, we can determine some characteristics of kilims design tradition.

In creating their designs, weavers depended on repetition and variation of a relatively small number of motifs, although the motifs themselves might not be small in terms of their physical size. Just to give you a sense of the size of these kilims, the longest ones can reach up to 14-15 feet long. The ones on the screen are about 10- 11 feet long.

Weavers expanded the design repertoire through a process of elaboration or simplification.

44 left

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.53, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 93 X 89 cm (36.5 X 35 inches)

*

*

43 right

*

*

Kilim, western Anatolia, early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, The

Textile Museum 2013.2.10, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 268 X 88 cm (105.5 X 34 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 44 left and right:

This was done by presenting the same motifs in different sizes.

45 lower (note red circled device in the border)

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, late 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced

plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft.

The Textile Museum 2013.2.1, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 374 X 84 cm (127 X 33 inches)

(again, note the same red circled device, now, in this turned view, on the left)

*

*

45 upper (notice red circled device now in the field)

*

*

Kilim, Central or western Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.67, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 173 X 71 cm (68 X 28 inches)

(red circled device is now prominent in the field)

*

*

Sumru:

This process of elaboration or simplification was also utilized when introducing new design ideas.

The introduction of new design elements had to start by using them as minor design elements, such as border designs, and had to move slowly to be used as main design elements, which were considered the most important signifiers of tradition.

Later on, the weaver could take the same design element from a minor element status, enlarged it and, artfully, make it into a main design element that dominated the whole kilim.

46

*

*

Sumru on 46:

They created layouts with design elements of equal or fluctuating emphasis, in which what was dominant and what was recessive, remains unresolved.

46 left

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.56, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 267 X 183 cm (105 X 72 inches)

46 right

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.78, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 157 X 107 cm (61.5 X 42 inches)

47

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, early 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.72, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 343 X 158 cm (135 X 62 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

The varying sizes of many reciprocal motifs, which form both negative and positive space, tease the eye. Either aspect of the composition can be the primary view, the other spaces receding into the background. This effect is known as “figure ground reversal”

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

48

*

*

Sumru:

The optical effects of figure ground reversal are compounded when the these kilims were draped over textiles or hung, or draped on top of one other, creating undulated surfaces. The eye shifts from angle to angle, textile to textile. Elements of the patterns appear similar, then different.

They move in and out of view with the kilims’ folds. The kilims dynamic drapery and large size obscures individual motifs. Dynamic properties and optical effects work in tandem and enhance each other.

That is why kilim weavers pay more attention to overall look than the individual designs.

49

*

*

Kilim (and lower detail), western Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit-tapestry weave, The Textile Museum, 2013.2.40, The Megalli Collection.

Sumru:

Another characteristic of designs seen on these kilims are the way they are visible and powerful from a distance, but also are very engaging when viewed at close proximity.

50

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.37, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 291.5 X 108 cm (117.5 X 42.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

The optical effects of figure ground reversal are compounded when the these kilims were draped over other textiles or hung, or draped on top of one other, creating undulated surfaces. The eye shifts from angle to angle, textile to textile. Elements of the patterns appear similar, then different.

They move in and out of view with the kilims’ folds. The kilims dynamic drapery and large size obscures individual motifs. Dynamic properties and optical effects work in tandem and enhance each other.

That is why kilim weavers pay more attention to overall look than the individual designs.

51

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, Konya, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave,

supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.63, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 404 X 96.5 cm (159 X 38 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

In good textile design, the relationship between positive and negative spaces, created through color, is always important.

Color transforms the overall sense of a textile, besides the mechanics of how a design is created.

Based on our observations of their products, we can confidently say Anatolian kilim weavers were deeply aware of this and took advantage of it.

Until the late 19th century, they had to work within the confines of a very limited palette based on available natural dyes.

But they still were able to produce unsurpassed effects of color by exploiting to the fullest this natural palette.

52

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.32, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 357 X 115.5 cm (140.5 X 45.5 inches)

*

*

52 middle

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly west-central, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.48, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 312.4 X 110.5 (123 X 43.5 inches)

*

*

52 lower

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly west-central, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.64, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 371 X 76 cm (146 X 30 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

Look back at 52 upper, middle and lower.

They wove the very same design with different colorways, creating kilims with entirely different feelings and looks.

53

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, Mid-19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft substitution, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.22, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 265 X 125 cm (104 X 49 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

The uncompromising and uncluttered design seen on many early Anatolian kilims leaves large areas of plain color exposed.

Weaver needs to rely on well-dyed yarns to achieve a good product and they usually did, at least the experienced ones.

This example stands out among the others, and is one of my favorites.

This carpet has a very sophisticated color palette.

It uses red, green, and blue, just like the Mamluk carpets produced in Egypt in the 15th century.

54 upper

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for some of the outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.47, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 395 X 75 cm (155.5 X 29.5 inches)

*

*

54 lower

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.34, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 389 X 66 cm (153 X 26 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 54 upper and lower:

Colors, of course, are the key to enhanced visual impact, with exploration of spatial possibilities. The relationship between positive and negative spaces, between foreground and background, have been always important in kilim weaving.

They juxtaposed colors, especially contrasting or complementing colors, to create dramatic effects.

Often we may feel that weavers pursued these effects at the expense of the legibility of motifs that so interest modern viewers, like us. We pay more attention to pattern/design.

55

*

*

55 left

*

*

55 right

*

*

Sumru on 55 left and right:

The weavers was very skillful in manipulating how colors appeared through the use of thin outline of another color that is distinct from both neighboring colors, which emphasized the demarcation between two color areas; this in turn enhanced the contrast between the adjacent colors.

56

*

*

56 upper

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.51, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 319.5 X 59.5 cm (125.5 X 23.5 inches)

*

*

56 lower

*

*

Bag (unconstructed), Western Anatolia, possibly northwestern, mid-19th century, wool, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping and patterning, knotted pile. The Textile Museum 2013.2.61, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 271 X 71.5 (107 X 28 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 56 upper and lower:

Anatolian women were masters of two distinct weave structures for two different functionalities.

Slit tapestry weave was used exclusively for kilims.

Supplementary-weft patterning, in its various forms, was used 90 percent of the time for weaving transportation/storage bags, such as 56 lower. in the slide.

57

*

*

Kilim (detail), central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 2013.2.54, The Megalli Collection.

*

*

Sumru:

Anatolian weavers seemed to accept the natural limitations and created the designs that fit with the structural constraints of slit tapestry weave.

They developed a design repertoire that was essentially rectilinear, geometric and nonrepresentational or abstract, while the original inspiration for the designs most likely came from the natural world around them.

Anatolian weavers took elements of the natural world and stylized and geometricized them, absorbing them into their own rectilinear grammar.

58

*

*

*

Sumru:

Textile researcher Marla Mallett has mentioned that it is important to consider the critical relationships between what she calls “weave balance” and patterns seen on the textiles.

Of course we need to keep in mind that every weave structure have its own “weave balance.”

This relationship is a vital part of the aesthetic development in tapestry woven textiles in general and in Anatolian kilims specifically.

The size relationship between the warp and weft yarns is one of the weave balance issue; in most old kilims, the weft is less than half as thick as the warp, usually loosely spun and not plied; while the warp yarns are 2 Z spun yarns S plied.

This way, weft yarns totally cover the warp yarns, creating solid color areas in pattern.

59

*

*

59 left

*

*

59 left: Kilim, eastern Anatolia, first half of the 19th century, wool, tapestry weave, The Textile Museum. 2013, 2.78, The Megalli Collection.

59 right

*

*

59 right: Prayer kilim, central Anatolia, late 19th century, The Textile Museum, 1964, 39.4, gift of Arthur D. Jenkins.

Sumru on 59 left and right:

Another weave balance issue is the necessity for achieving a balance between using enough slits to create motifs and limiting the length and frequency of slitting in order to maintain structural integrity.

This of course has had a profound influence on the pattern or character of kilim designs.

60

*

*

Sumru:

It is harder to achieve minimalist work, than a highly decorated one. A good and experienced weaver knows that.

You need to pay attention to your wool, color, tension and technique.

Color change and not creating long slits forced her to do minor adjustments which can be only detected if stop looking at the design and try to figure out the technique.

The reason I study textile structures is that I can that way see weaver’s hand. For me it is in the structure, more than the pattern that one comes close to the weaver and her thinking.

61

*

*

Kilim (detail), central Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave , The Textile Museum 2013.2.3, The Megalli Collection.

*

*

Sumru:

Slit tapestry weave creates crisp vertical definitions between color areas, and often weavers incorporate the slits into their overall design.

Need to respect slits!

62

*

*

Kilim, western Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave , The Textile Museum 2013.2.38, The Megalli Collection.

*

*

63

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, Afyon, late 19th century, wool, cotton, slit tapestry weave, weft substitution, weft float weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.5, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 228 X 115.2 cm (89.5 X 45 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

Any kilim that is wider than 90 cm was woven most likely by two weavers in a wide loom or she was willing to lift herself up occasionally to move to the other side of the kilim.

The wide looms were generally built in place and not easily portable; a village home is a better set up for larger looms.

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the one below to get a larger version.

64

*

*

64 lower right

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.71,The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 364 X 90 cm (143 X 35.5 inches)

64 left

*

*

Sumru on 64:

Weaving orientation vs use orientation

Howe comment: Kilims are woven with the long side vertical, as in the image above. But kilims are usually used with the long side on the horizontal. Most kilim books choose to present kilims with the long side vertical. As you have seen in this virtual version of Sumru’s talk, we have honored both of these usages. We have initially presented each piece with the long side horizontal and then have a second image turned to let you see it with the long side vertical. This has the further advantage of letting you see a larger image of each piece.

64

Photo shows kilim being woven with long side vertical, while kilim in use ,on the left, has its long side horizontal.

*

*

65

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, early 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.82, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 271 X 77 cm (106.5 X 30 inches)

Sumru:

The two big questions that occupy Anatolian kilim studies are when and where kilim weaving began in Anatolia? and when and where Turkmen started weaving kilims?

At the beginning of the 13th century, when Anatolia was under the control of Selcuk Sultanate of Rum, Geographer, historian, and poet Ibn Sa’id al_Maghribi (d. 1274 or 1286?) gave an account of Yörüks. He mentions that Yörüks wove for their own purposes as well as to sell. There were about 200,000 Türkmen tents near Denizli in western Anatolia and they traded kilims, slaves and lumber. Between Ankara and Kastamonu, there were about 100,000 Türkmen tents. Caution is necessary to interpret what Ibn Sa’id might have meant when he used the term ‘kilims’. He might be referring to knotted-pile carpets.

If we accept Ibn_Said that kilims were being woven in Anatolia in the 13th century, when and where did they first appear in the region?

66

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.13, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 314 X 102 cm (123.5 X 40 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

There are two theories about the origin of the kilim weaving in Anatolia. One is the Turkmen theory.

This theory argues that kilim weaving and its designs were brought with Turkish migration from further east.

Anatolian kilim tradition was an outgrowth of a cultural continuum centered around the culture of Turkic people, while it might have also included other influences,

*

67

*

*

Sumru:

The second theory is the goddess theory, which argues that kilim weaving and its designs were native, and predate Turkish migration.

Adherents to this theory believe that despite all of the cultural transformations through which Anatolia passed over the millennia, the kilim weaving tradition indicates the survival of indigenous populations who preserved the old beliefs and ways.

Howe:

Immediately below, are separate images of 67. The first is the lower image from the slide above and is the complete piece with its caption.

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, dovetailing. The Textile Museum 2013.2.70, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 388 X 147 cm (152.5 X 57.5 inches)

*

67 end fragment turned

*

*

68

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning (removed). The Textile Museum 2013.2.45, The Megalli Collection

Dimensions (warp x weft): 323 X 140 cm (127.5 X 55 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

There are still myriad questions that need to be answered before one of these theories can be proven correct.

Many of these questions surround the Turkmen migration to Anatolia and the origin of kilim weaving:

Exactly what kind of weaving technology, technique, and design tradition did Anatolia have by the time of the great Turkmen migrations?

What kind of weaving tradition did the Turkmen carry with them when they migrated?

69

*

*

Sumru on 69:

Although concrete evidence is still scarce, several scholars has begun slowly investigating the history of the region pre- and post-Turkish arrival with revived interest in the pre-Mongol history of art of Seljuk Anatolia. We know very little about the Turkic nomads that migrated into Anatolia. Their histories, if written at all, were primarily written by others—mostly Persian and Arab bureaucrats and scholars—and the elite urban literati did not have any interest in the social or artistic output of the nomad groups moving through Iran and settling in Anatolia.

Was there in either or both populations a kilim tradition that could be regarded as the ancestor of what has become known as the Anatolian kilim?

How did these two traditions interact in Anatolia once the various nomadic groups began their long process of assimilation and coexistence?

70

*

*

Right: Hanging, Egypt, 4th to 5th century, wool and linen, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 71.118, acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1950

Upper left: Textile fragment (tiraz), Egypt, Fatimid period, 10th century, linen or cotton, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 73.549, acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1947

Lower left: Textile fragment (tiraz), Egypt, Tulunid period, late 9th century, wool and linen, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 73.572, acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1948

Sumru on 70:

In terms of tapestry weaving, there is clear evidence that it was carried out in West Asia, long before the Turkish nomads arrived. This evidence includes early Islamic textiles as well as much earlier late Roman and Byzantine textiles.

Although the technique was not foreign to the region, when the Turkish nomads arrived, there is no surviving example with designs that could be considered clearly precursors of Anatolian kilim designs.

There also is no surviving evidence informative enough about the types of designs and weaving techniques used by the Turkic nomad weavers, and what they brought into Anatolia in the 10th century.

Howe: Below are larger versions of the parts of 70 sequenced from the oldest to the youngest. To repeat the indications in the captions, all three were done in slit tapestry weaves. But the designs are all different from those we see in Anatolian kilims.

Right side of 70

*

*

Right: Hanging, Egypt, 4th to 5th century, wool and linen, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 71.118, acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1950

Howe: This piece is from the informally-called “Coptic” period: 3rd to the 7th century. Copts were Christians. Coptic Eygpt was ruled by a Mandarin-like group of Central Asians, kidnapped as children, and then raised and trained for that purpose. Islam invaded Eygpt in the 8th century.

*

Lower left of 70

*

*

Lower left: Textile fragment (tiraz), Egypt, Tulunid period, late 9th century, wool and linen, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 73.572, acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1948

The Tulunid dynasty: Turkic in origin, was the first independent dynasty to rule Egypt and Syria, 868-905.

*

Upper left of 70

*

*

Upper left: Textile fragment (tiraz), Egypt, Fatimid period, 10th century, linen or cotton, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 73.549, acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1947

*

71

*

*

Sumru on 71:

One issue always comes up in kilim studies is the symbolism.

We can posit that the designs on long kilims were expressions of weavers’ personal histories.

A textile can function as a document of weaver’s memory, a host of symbolic reminders of her family and friends, an abstract portrayal of social affinities she developed during the creative process of weaving, and only know to her and close kin.

Since the associational meanings died with the weaver and her family, it is impossible to rebuild the personal meanings invested in a given kilim.

Howe: Large versions, with captions, of the pieces in 71.

Upper 71

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, late 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave. The Textile Museum 2013.2.2, The MegallI Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 328 X 79 cm (129 X 31 inches)

*

*

Lower 71

*

*

Kilim, central Anatolia, 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum 2013.2.28, The Megalli Collection

*

*

72

*

*

Sumru on 72:

Frequent use of certain design layouts and motifs might point to the fact that those layouts and motifs were special to the society in which the weaver lived

Then the question is how to identify motifs remotely indicative of self-expression in kilim’s design. The only likely elements in the kilim design, which were not prescribed by the culture or tradition,

73

*

*

Sumru continues on 73:

were randomly appearing motifs that were woven with supplementary-weft yarns or small tufts of colorful wool or human hair that were knotted. These motifs might be the only candidates to be considered as weaver’s self-expression.

They were never woven to be a logical part of the overall design, or had any clear and continuing relationship with design layout, or even with other motifs. Their presence did not support the large coherent statement kilim weavers expected to make.

This leaves only one option open and that is that weavers incorporated these motifs as reminders or memory aids for the events occurring around them and they wanted to remember. What those events were, however, may never be known.

Larger versions of the images in 73.

73 upper

*

*

73 lower

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.38, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 338 X 82 cm (133 X 32 inches)

*

*

74

*

*

Kilim, Eastern Anatolia, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.77, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 383 X 84 cm (150.5 X 33 inches)

*

Sumru on 74:

It is extremely hard to date and provenance Anatolian kilims, especially ones predating the 1870s.

They were:

#1 created by very conservative nomadic societies, and

#2 used in very harsh environments, preventing large survival rates.

Anatolian kilim weaving is a traditional weaving, which meant that it was highly conservative in its use of the same designs over multiple generations.

The relative isolation of nomadic groups from mainstream cultural and aesthetic events of the Ottoman Empire was another important reason for this conservatism.

Change in glacier terms. What does this refer to?

74 turned

*

*

75

*

*

Kilim, Southern Anatolia, early 18th century – early 19th century, wool, cotton, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.57, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 385.5 X 155 (151.5 X 61 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 75:

Many surviving kilims, in known collections, date to the period from the late 17th century, to the early 20th century.

The relatively late date of surviving kilims makes them not very eligible for conducting accurate radiocarbon dating, although there are attempts to do that in Europe especially by Jurg Rageth.

Carbon 14 dating for 75, above, indicates that it was 54.1% likely that it was produced between 1712 and 1821., And 1661-1708 (18.6%) and AD 1835-1880 (8.2%) likely. Overall calibrated age has 95% confidence limit.

76

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, c. 1900, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, supplementary-weft patterning, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.92, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 400 X 177 cm (157.5 X 70 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 76:

The reasons for the small survival rate of this material are threefold.

Kilims, compared to carpets, were used more heavily and in an environment that is harsh to the textiles.

Thirdly, slit tapestry weave creates a lighter fabric that can be carried around easily, but it does not create a sturdy textile that can stand continuous heavy use.

Remember to click, sometimes more than once, on smaller images like the ones below to get a larger version.

77

*

*

Sumru on 77:

In terms of giving provenance to these textiles, the difficulty arises from the way nomads live. They move continuously, sometimes splitting into smaller groups and sometimes reconnecting. There are few nomadic groups in Anatolia whose centuries-long movements were accurately documented. The Aydinli nomadic group is a good case study to illustrate this fact.

Let’s look, first at these two kilims in 77.

*

77 upper

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, probably Aydin, first half 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave,

supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.9, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 362 X 78.5 cm (142.5 X 31 inches)

*

*

77 lower

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.71, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 364 X 90 cm (143 X 35.5 inches)

*

*

Sumru:

Now about the Aydinli nomadic group who wove these two kilims.

Look at the map below and locate the small red dot in its lower left.

78

*

*

Sumru on 78:

This where a group of nomads, who considered themselves part of Aydinli nomads, lived in southeastern Anatolia in the late 20th century. Ottoman officials first recorded them in the western Anatolia, in the environs of Aydin in 17th century.

Over the next two to three centuries, they moved eastward for various reasons. They first moved to central Anatolia and

*

79

*

*

then to their current location in southeastern Anatolia (see larger red mark in the map above).

Along this two-century long move, some members of the group broke off and settled. Others continued their migrations into different parts of Anatolia. Of these, some settled, some did not, until the 20th century.

Because of this movement, we can identify various communities across Anatolia weaving very similar designs, that are considered part of the Aydinli design repertoire. But it very hard to say, accurately, what the provenance of this group’s kilims are, when they are collected out of context.

80

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, late 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.11, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 347.5 X 76.5 cm (136.5 X 30 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 80:

The way of life in nomadic communities in Anatolia has changed dramatically, especially during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Only the kilims are left as enduring records of that life.

Their history spans at least five centuries, and they present wide stylistic variety. In addition to that, they were created by societies where oral tradition is the norm compared to the literary tradition of urban societies. All these facts make analyses of kilims, and the weaving tradition associated with them, far more complex.

81

*

*

Sumru on the pieces in 81:

Still, there is hope! We know that kilims are a potent expression of the nomadic and peasant culture in Anatolia as well as a highly personal expression of rural women.

But, they also were molded by a profusion of powerful aesthetic influences, originating from the many ethnic groups that make up the Anatolian culture.

In addition to that, the influence of the high Ottoman culture is evident on many kilim designs, although this influence might have not been very direct.

Larger versions and captions of the images in 81.

81 left is a detail image

*

*

Here is an image of the complete 81 left, with caption.

*

*

Kilim, western Anatolia, late 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, The Textile Museum, 2013.2.87, The Megalli Collection

*

81 right

*

*

Kilim, Western Anatolia, late 18th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, supplementary weft wrapping for outlines, supplementary-weft patterning. The Textile Museum 2013.2.87, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 131 X 106 cm (51.5 X 41.5 inches)

82

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, second half 18th century, wool, cotton, slit tapestry weave, weft-faced plain weave, eccentric weft. The Textile Museum 2013.2.3, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 342 X 137 cm (134.5 X 54 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 82:

During my long examination sessions of these kilims, I became aware that while 20th-century collectors and scholars shaped the knowledge about Anatolian kilim around decorative motifs, nomads who produced and used these appear to highly valued the material and technical characteristics of kilims.

Decorative motifs were significant to nomads, but not necessarily more significant than other factors.

Many of the decorative motifs are also brought about directly from material and technical characteristics of kilims. In short, we can posit that because nomads were so intimately connected with the weaving process, their value system contain elements that are more central to the process, and as a result different than contemporary view that values primacy of pattern and motif.

83

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, possibly west-central, 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines, eccentric weft.The Textile Museum 2013.2.17, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 336 X 171 cm (132 X 67 inches)

*

*

Sumru on 83:

Since no contemporary aesthetic treatise on Anatolian kilim is known, proof of this assertion can only come from thorough analysis of the textiles themselves.

By tracking the most commonly emphasized features of kilims, it is possible to ascertain which material and technical characteristics were most valued by their weavers and users.

Field research conducted by scholars in the twentieth century among the few nomads left, help us today piece to gather some of the ways these old kilims might have been used, but again I am cautions about using them as the final word.

84

*

*

Kilim, Central Anatolia, 19th century, wool, slit tapestry weave, supplementary-weft patterning, supplementary-weft wrapping for outlines. The Textile Museum 2013.2.90, The Megalli Collection.

Dimensions (warp x weft): 367 X 88.5 cm (144.5 X 34.5 inches)

*

*

Although work on deciphering of Anatolian kilims is ongoing, there is no denying that Anatolian kilims, with their bold but simple coloration, large scale, and skillfully balanced designs have a very strong visual power for contemporary eyes who value pattern.

The beauty and mystery that surround their origin, history, and design, serve to amplify this aesthetic power.

We need to always remember that there is more to kilims than the eye sees.

Sumru took questions

and brought her session to a close.

My thanks to Sumru for this fine session and for her considerable work, after, helping me fashion this post.

We sometimes feel, a bit selfishly, that curators do not give RTAM presentations as frequently as we would like. But Sumru has not only done so, she has, without embarrassment, let us look over her shoulder as she works with material that will be presented in final form in an October exhibition.

As you have seen in her remarks above, she invited thoughts that folks in the audience might have, that might be useful to her. Although we’re close to opening of this exhibition, if you have some, as the result of reading this post, write me with them and I’ll send them to Sumru.

I hope you have enjoyed this advance look at Sumru’s work with beautiful, Anatolian kilims from The Megalli Collection.

Regards,

R. John Howe

You must be logged in to post a comment.