On January 30, 2016, Brooke Jaron,

*

*

gave a Rug and Textile Appreciation Morning program on:

*

Brooke is a textile historian and artist who will help us interpret the symbolic language of Chinese textiles. Brooke will discuss examples ranging from home-crafted children’s hats and clothing to purses and fan cases by the imperial workshops of Qing dynasty China.

Brooke is also a collector of Asian textiles and antiques. She has lectured and written numerous articles on the subject of symbolism in Chinese textiles. Her latest article on the “year of the Monkey” appears in the January issue of “Textiles Asia Journal.” Recently, she participated in the Textile Museum’s first-ever Pecha Kucha presentation during its annual Symposium, with a talk on the symbols of the Chinese zodiac. She also designs jewelry.

This is Brooke speaking:

*

*

For the past 30 years I’ve been collecting Chinese textiles. Most of them were purchased during the more than 40 trips that my husband and I took to China between the early 1980s and the present. I noticed early on that there were images that appeared on many different articles and I began to wonder why it was that there were so many bats, or cranes or odd looking old men with huge foreheads. What started out as curiosity, eventually led me to many years of asking questions, studying whatever material was available, and trying to decipher the hidden meanings in the pieces I gathered in my travels.

*

*

The Chinese have for centuries believed that by surrounding themselves with lucky objects and images, they would increase the likelihood of a happy, healthy and prosperous life. Over the years, a language of symbols has evolved, images that we can find repeated in the art they created, the buildings they lived in, the household goods that they used every day, and most particularly in the clothing and ornaments that they wore and carried.

The Chinese spoken language, Mandarin, is made up of many one or two syllable words with a similar or identical sound, although the written characters are not the same. Many of the symbols are based on these homonyms and when several are combined, they form a rebus. This is an example of a rebus in English.

*

The eye and the ewe are different words that sound the same as I and you, and the heart is an easily recognized substitute for the word “love”.

*

*

During the Qing Dynasty, which stretched from the 17th to the early 20th century, these rebus-based symbols appeared in all areas of daily life. There were also other symbols that were based on folk tales, associations with mythical characters, and the practice of assigning symbolic meaning to various objects, fruits, flowers and animals. These symbols would have been recognized and understood by almost all of the population, and their application was especially appropriate in a society where many people did not read or write.

The image of five bats is an example of a symbol based on a homonym. The word for bat is bian fu, or fu for short; the word for luck, good fortune or blessing is fu, so identical in pronunciation.

*

The image of five bats is an example of a symbol based on a homonym. The word for bat is bian fu, or fu for short; the word for luck, good fortune or blessing is fu, so identical in pronunciation.

Five bats represent 5 blessings; the original five: longevity, health, wealth, a virtuous life and a natural death were first mentioned in an ancient text from the Warring States period, approximately 450 BCE.

*

*

Later, the five blessings became less specific, meaning “may every blessing come to you.” Among the possible choices for the five blessings, we’ll look at those most commonly depicted on textiles: good fortune, longevity, prosperity, happiness in marriage and many children.

*

*

Most of the representations of the five blessings/ five bats motif have the Chinese character Shou in the center.

*

*

Shou is a decorative variation on the character for longevity. Of the five blessings, long life represents the greatest wish of the Chinese people, so it is not surprising to see a doubled wish for long life in this popular design.*

*

*

*

A single bat is a symbol of general good fortune and luck.

The bat is often pictured in a descending pose with head down. The Chinese word for upside down, dao, has the same sound as the word meaning “has arrived,” so an upside down bat means Fu Daole “good fortune has arrived.”

*

*

Two bats facing each other represent “double luck” Shuang Fu, and may be found on clothing and objects created for weddings.

A bat descending over an ancient coin means good luck before your eyes because the word for the square opening in the old coins sounds the same as the word for eye and the word for “coin” or “money” sounds like “in front of”. So Fu Zai Yan Qian illustrates a popular four character saying meaning “good luck before your eyes”.

This child’s hat has two bats descending over the ancient coins, as well as many other auspicious symbols for longevity and fertility.

*

*

On the back of another child’s hat, we see a silver ornament with the same image and meaning “good luck before your eyes”.

*

*

Although the bat is the most common symbol for good fortune, there are other emblems that would have also been recognized as wishes for good luck.

*

*

The dragon, unlike the dragons in western cultures, has always been considered an extremely lucky image in China. The mythical dragon was a creature that inhabited the skies and was believed to be responsible for the bringing of rain, and the resulting good harvest.

*

*

This embroidered panel shows a successful scholar posed in front of a very friendly looking dragon. The four characters in the corner are Fu Gui Ru Long, which mean “Wealth and Honor like the Dragon.”

The tiger was also considered a lucky animal and a great protector against all types of evil forces.*

*

For that reason, we see many tiger depictions on clothing and hats made for children. *

*

*

*

The character Wang on the tiger’s forehead means “king,” because in China the tiger was considered the king of beasts.*

*

*

The word for “vase” Ping An sounds like the words for safety and peace, so the vase with various things inside of it was popular design motif; here it’s seen on a silk pillow end

*

*

and also shown on a small purse*and a card case both of which would have hung from a man’s belt.

The top of the ruyi scepter is a symbol meaning “as you wish” so it can appear with other auspicious objects or stand alone to mean “whatever your desire may be, let it be as you wish.” * This child’s hat has a ruyi shape on the back .

*

*

The actual scepter was made of carved wood, various stones, ivory or in this case, gold. It was often given by the emperor to high ranking officials as an acknowledgement of their service.

The Buddha’s hand citron is a fruit that looks like the hand of Buddha

*

*

*

The Buddha’s hand citron is a fruit that looks like the hand of Buddha.

The name in Mandarin is fo shou which is a literal translation of Buddha Hand. It’s similar in sound to Fu, meaning luck and Shou meaning longevity, so because of this, it is a symbol of luck and long life. The foshou is often shown with the peach and the pomegranate .

*

The three fruits represent the Three Plenties: Good Luck, Long Life and Many Children.

*

*

The desire for a long life ranks high among the five blessings and there are many symbols representing the wish for longevity. As we saw in our examination of the five bats/five blessings images, Shou, the stylized Chinese character for longevity, is often placed in the center of the circle of bats.

Shou is also a popular emblem by itself and can be found on many varieties of textiles.

*

Here we see a set of belt hangings created in a professional workshop, possibly even made for members of the court. The set includes a pair of scent pouches, a card case, a watchcase and a box for holding a carved stone archer’s thumb ring.

*

*

*

An eyeglass case was probably once part of an equally elegant and elaborate set.

Sometimes instead of using the character shou in a design, the wish for longevity is conveyed by the mythical figure Shou Lao,The God of Longevity. *

He can be recognized by his large forehead, and white beard. He is usually holding a peach and a tall staff, and accompanied by other symbols of longevity such as the pine tree or deer.

*

*

The pine tree and the crane are both popular longevity symbols and they are often shown together.* Ancient pine trees can be found in many parts of China where they are cared for and honored.

*

*

The crane with its white feathers was reputed to live for many years.

*

*

The pine and crane together form a popular birthday greeting meaning “May you live as long as the pine and the crane”. This motif is also used on wedding gifts as they can also be symbolic of the bride and groom.

*

*

The deer is another common longevity symbol; it is the only animal capable of finding the Lingzhi fungus, which is known as the fungus of immortality. The deer and a stylized version of the fungus are frequently shown together.

*

*

In this embroidered panel we can find three of the most common longevity symbols: the deer, the pine and the crane.

The peach, which we have already seen as one of the fruits in the Three Plenties, is a longevity emblem that appears alone and also in many combinations. It is found in virtually all areas of Chinese art decorative, including porcelain, wood and ivory carvings, silver ornaments and all types of clothing and accessories.

*

*

In an ancient legend, the Queen Mother of the West had a heavenly orchard with peaches that ripened only every 1000 years. Eating one of these peaches would insure immortality.

The image of the monkey with the peach is based on an occurrence in the fantasy adventure novel “Journey to the West” in which one of the characters, the monkey king, stole magical peaches of immortality from the Queen Mother of the West. The novel, which was written in the 16th century, was considered one of the four great classical novels of China and was also widely performed by story tellers, shadow puppet troops and regional opera companies all over China. Because of the popularity of the story, Sun Wu Kong, the Monkey King, was an easily recognized character and a symbol of immortality.

*

*

This is a painted, appliqued and embroidered monkey on the back of a child’s hat. We can identify him as Sun Wu Kong, by the fact that he is wearing a vest and also because of the two very large enormous peaches he is sitting between.

*

*

The eight immortals are well known figures of a more serious nature. These seven males and one female figure represent the Daoist ideal of immortality. They appeared in the 13th century as paintings on the ceilings of tombs, but in the Yuan Dynasty, their popularity spread and they have remained, as an easily recognizable group until the present time.

*

*

The two sides of this hanging pouch have embroidered depictions of all eight of the immortals.

*

*

Sometimes only the attributes of the immortals are shown, but they would also have been familiar to most people in the Qing Dynasty.

The butterfly is a motif associated with summer and romance. It also has symbolic meaning based on the sound of the word in Mandarin, which is hu die. The second syllable of the name, die sounds the same as the word for septuagenarian.

*

*

It also sounds like the word for continuous, so as a symbol, the butterfly means “may you continue to enjoy longevity into your 70s.”

*

*

The shrimp is another symbol for long life based on a homonym. Shrimp in Chinese is xia and the word for advanced age is xia, so almost the same, except with a different tone. While the butterfly was a popular motif on gifts for older women, the shrimp was its counterpart for men’s gifts.

In addition to longevity, prosperity was also one of the primary desires of people in the Qing Dynasty. Consequently there are many symbols for Lu, the Chinese word for prosperity.

*

*

Although written differently, the word Lu is also the name for deer, so in addition to being a symbol of longevity, the deer is a symbol of wealth and success.

Lu literally translates as “official’s salary” because in the Ming and Qing dynasties, becoming an official was one of the only ways for a young man to gain status and wealth. Beginning in the Song Dynasty, a system of national examinations was put in place. A young man from any station in life was eligible, and anyone who could do well on this examination would be awarded a position in the government. Those with the highest scores would even have a place in the government of the Imperial court. There are numerous symbols connected with passing the examinations and bringing honor, prestige and wealth to one’s family and village.

*

*

The horse became an emblem for success in the examinations because the winning candidate would often return to his hometown on a white horse.

There are many depictions on textiles showing a young man, mounted on a horse or resting beside his horse, and often wearing the mandarin’s hat that would identify him as an official.

*

*

On this purse flap we see five little boys playing together with a military helmet. The helmet kui is a homonym for the word meaning eminent or great, a word that was used to describe the one who placed first in the Imperial Examination.

*

*

The five boys refer to the five sons of a scholar who lived in the 10th century and raised five sons who all had the highest marks on the examination.

*

*

This red silk dudou shows a scholar wearing his official’s hat and standing on the head of a mythical dragon-fish, known as an Ao. This was another symbol to describe gaining first place in the final civil service examination. The candidate who captured first place in the exam was known as the one who stood on the head of the ao. A four character saying du zhan ao tou meaning “seizing Alone the head of the Ao” was used to describe this accomplishment.

*

*

I’ve mentioned several four character sayings, known in Chinese as cheng yu. These are similar to our proverbs and many of the symbols represent these well known sayings. Li Yu Tiao Longmen is another cheng yu which means Carp Jumps Over the Dragon Gate.

In an ancient Chinese myth, a carp that could swim upstream in the Yellow River and jump over the rapids at the dragon gate would instantly be transformed into a dragon. This was a well known metaphor for a scholar passing the Imperial examinations.

*

*

The rooster was also several associated with success and prosperity.

*

*

The word for rooster in Mandarin is gongji. The first syllable gong sounds like an official rank, “duke’, while the second syllable ji sounds the same as the word for “good luck”.

*

*

*

The crab is yet another symbol for passing the national examination with high marks.

The word for the crab’s shell jia is the same as the word meaning first place. One crab, yi jia ,means finishing in the group of fist place candidates and two crabs is er jia would be the second group.

*

*

The peony is the most popular botanical motif in China. One of the names for this flower is fuguihua, which literally means “wealth and honor flower.” It has been a symbol of success since the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century. It is often combined with other auspicious symbols to form a more complicated and comprehensive

message.

*

*

The cricket or katydid is a symbol of prosperity and success.

*

*

*

It is usually depicted with a cabbage, baicai or lettuce shengcai, both prosperity symbols because cai the second syllable of each vegetable name sounds similar to the word cai which means wealth.

*

*

The gold fish is a popular motif in Chinese art. Keeping live fish, either inside the house or outside in ponds is a common practice.

The name in Mandarin, jinyu is an exact translation: Jin meaning gold and yu meaning fish. A reference to gold creates an obvious emblem of wealth. Yu the word for fish sounds like a word meaning abundance, and yu, with a different tone is the word for jade. So, the goldfish as a symbol is either abundant gold or gold and jade.

*

*

We’ve seen symbols of high position, wealth, gold and jade in our examination of prosperity symbols, but we cannot forget to mention the humble pig as an emblem of wealth and comfort. During the Qing Dynasty, China was primarily an agricultural society and having a pig in the yard (or in the house) was a guarantee of food for the winter and throughout the year. In ancient Chinese script, the character for home was a pictogram showing a pig under a roof, so it has always had the connation of comfort and abundance.

So, we’ve covered the first three of the five blessings. These are Luck, Prosperity and Longevity, Fu Lu Shou. They are often represented together as the three star gods, Fu Xing, Lu Xing and Shou Xing.

*

*

Next time you’re n a Chinese restaurant take a close look, especially at the entrance. If you see three statues of imposing Chinese figures you can be pretty sure they’re the three star gods, Fu Lu and Shou.

Beyond the big three, there are several other groups of popular auspicious motifs to be found in Chinese textiles.

*

*

The Chinese word Xi represents happiness and most particularly happy marriage. Arranged marriages were the norm in Qing Dynasty China. Marriage was sometimes a way to bind powerful families together for political reasons, or to raise the status of the family by having the daughter marry an official, or is some cases, sadly, just a means of relieving a family of the burden of supporting a daughter. Once a girl left her home to marry, she became a member of her husband’s family and on some cases did not return to the home of her parents. Only a son stayed close to his parents, usually living with his wife and children in the same house.

*

*

You have probably seen the double happiness characters, Shuang Xi on everything from porcelain to paper cuts. Red cutouts of the double happiness were used to decorate everything connected with weddings.

*

*

A pair of magpies has the same meaning as the Shuang Xi double happiness characters. The name of the bird in mandarin is xi que so literally, the bird of happiness.

If a magpie is shown on a branch of a plum tree, the message is happiness before your brow, because the word for plum, mei sounds like the word for brow.

*

*

This small hanging may have decorated a wedding bed, or have been suspended from the buttons on a bride’s clothing.

*

*

Mandarin ducks are known to mate for life so they are a good example of fidelity and happiness. If the ducks are shown with the lotus, which is a symbol of many children, then the symbolic meaning is a happy marriage blessed with many children. If a magpie is shown on a branch of a plum tree, the message is happiness before your brow, because the word for plum, mei sounds like the word for brow.

*

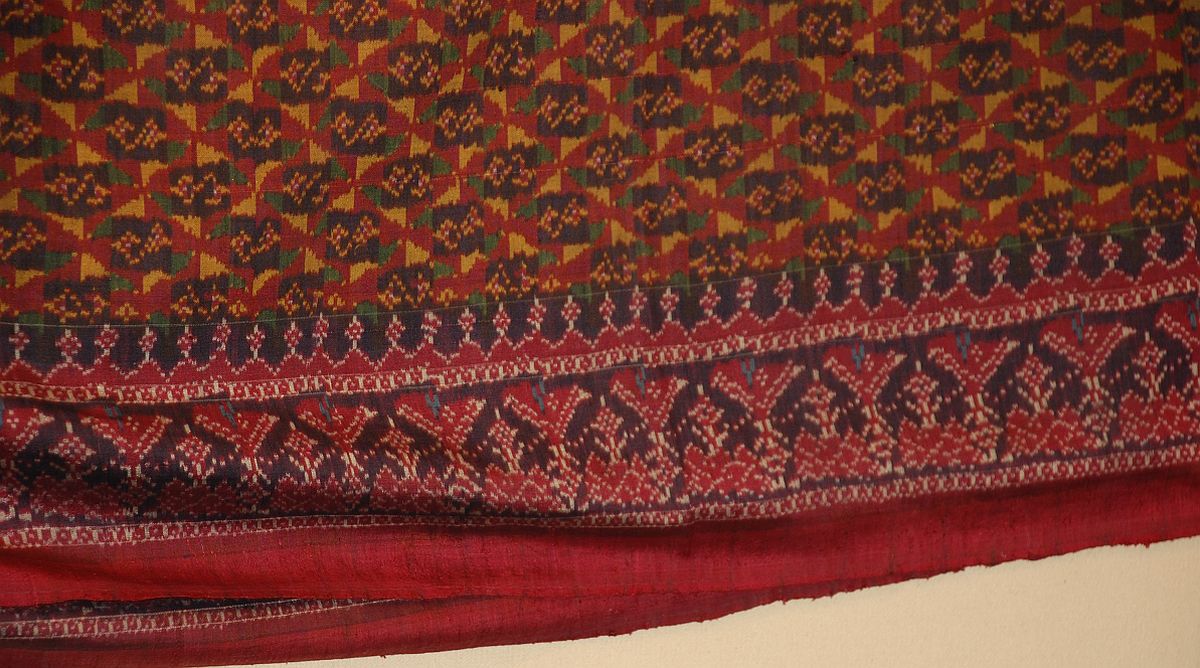

The dragon and the phoenix are two mythical animals, both representing good luck. The dragon represents the Yang principal in Chinese cosmology and the phoenix represents Yin. Together they form a balance between Yin and Yang and they also represent the emperor and empress. They were a very common motif for wedding attire in the Qing Dynasty, usually embroidered on a background of red or rose silk, the colors of celebration.

*

*

The word for fish yu sounds the same as the word for abundant. A rebus is formed when two carp are shown hanging below a stone chime. The word for an ancient chime, qing, sounds like the word for joy and happiness, so the two fish with the chime would be recognized as “May you have Abundant Happiness and Joy”. * A pair of carp also symbolized love and harmony because they often swim in pairs. The four characters, Fu Gui You Yu, mean “Wealth and Honor in Abundance.”

*

*

The last group of symbols that we’ll look at today are those that express the wish for many children, especially many sons. In Qing Dynasty China it was important to have sons for several reasons. China was mainly an agricultural nation and sons were needed to do the work necessary to maintain a farm. Secondly, in order to advance in society, only a son could hope to study and receive high marks on the Imperial Examinations. The most important reason was that a son would stay with the family after marriage, perpetuate the family name and perform the necessary rites to worship the ancestors.

Fruits, especially those with many seeds, provide a large number of symbols for many children.

The word for seed zi sounds like the word for child, or son, so any fruit with seeds is a symbol of fertility.

*

The melon, a popular fruit image, is depicted on this little girl’s band hat, and also on the spectacle case. The vine which surrounds the melon is an additional symbol meaning continuous, so the message we can read here is “continuous birth of children (or sons).”

*

*

Grapes are also a symbol of fertility. In the Qing dynasty, the seedless grape had not yet been developed. Often shown with a rat or squirrel, the grapes and rat are a symbol for many children.

*

*

The pomegranate, which is a fruit made up almost entirely of seeds, was perhaps the most popular child related symbol, at least among the fruits.

*

*

*

As we saw earlier, it is frequently combined with the peach and the Buddha’s Hand citron to form the motif known as the Three Abundances: a hope for many children, many years of life and many blessings.

*

*

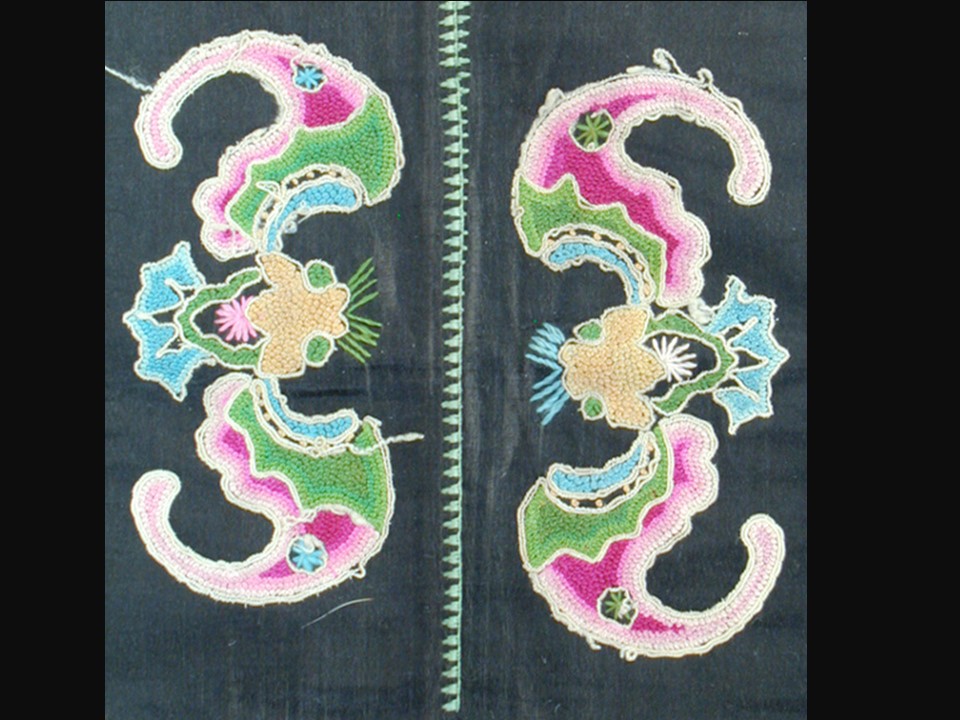

This is another set of belt hanging purses. These elegant sets were made in workshops where accomplished embroiderers were employed. All of the work was, of course, done by hand, but there may have been one person doing the embroidery, one stitching up the purses, another adding the trims, fringe and hanging ribbons.

*

*

Although not a fruit, the lotus has many small seeds, so it is also a symbol for many children. It has additional meaning because the name of the lotus, lian is a homonym for “continuous”. The lotus seeds, called lianzi sound the same as words meaning continuous sons. A child with a lotus has been a popular auspicious motif since the Song Dynasty, the 10th through the 13th century.

*

*

*

*

This elaborate and amazing child’s hat has a giant lotus blossom on its crown.

*

*

Perhaps the easiest design motif to interpret, is the depiction of groups of children that symbolize the wish for many sons. A popular theme is 100 Boys, which you may have seen in paintings or on porcelain vases. The number didn’t have to actually be 100 to express the same wish.

*

*

The Qilin is a mythical animal which has the body of a deer, the forehead of a wolf, the tail of an ox and the hooves of a horse. It also has either one or two horns and blue or green scales covering its body. It’s a popular subject for sculpture, paintings, silver ornaments and clothing. If you’ve ever visited the Summer Palace in Beijing, you may remember the large statue of a Qilin at the entrance to the park. The qilin is a powerful emblem of good luck, said to appear only when a benevolent and virtuous ruler is in power. In myths and legends, it was the bringer of sons, and not just ordinary sons, but illustrious sons who would bring honor to the family.

*

*

*

*

We’ve now seen examples of the five blessings in many different kinds of textiles. Symbols for good fortune, longevity, prosperity, happy marriage and many children have all been represented. I’d like to close with one of my favorite pieces* a rather humble embroidered pillow cover section, undoubtedly made at home, possibly as part of a bride’s dowry. Although it’s certainly not the most elegant or valuable piece in the collection, I think it has great humor and charm. It reminds me of the British author Roald Dahl’s children’s book “James and the Giant Peach.” It also makes a suitable ending to our exploration because it shows symbols representing all five blessings in one picture. We see a bat which represents good fortune, the giant peach stands for long life, a child expresses a wish for a successful son, the stone chime symbolizes happiness and joy and a pair of fish represent the traditional new year’s wish nian nian you yu “May you have abundance year after year.”

On February 8th we’ll enter a new year in the Chinese calendar, the year of the monkey. It’s only a little over a week away, so I’d like to be the first to wish you a very happy new year. The Chinese have several greetings for New Year. One is Gong Xi Fa Cai which means “Have a Joyous and Prosperous New Year.” The other is Xin Nian Kuai Le which is just a simple “Happy New Year”.

Brooke took questions and brought her session to a close.

*

*

Thanks again to her for working with me, after a long hiatus, to let you enjoy this excellent program.

‘Til next time,

R. John Howe

You must be logged in to post a comment.