On November 1, 2008, Bob Emry

gave a Rug and Textile Appreciation Morning program here at The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C. that dealt interestingly with buying rugs and textiles on the internet.

The specific title of Bob’s RTAM program was “From Turkey to Turkestan Virtually: Rugs and Textiles from the First Decade of eBay.” And while he and those in the audience included rugs bought on the internet, but not on eBay, the rugs and textiles Bob presented himself had all been bought there.

Bob began with some cautionary comments about buying on the internet, and on internet auctions like eBay in particular.

First, it is recommended that unless you have some real knowledge of and experience with them you should not buy rugs and textiles on the internet at all. There are too many ways to end up with something that will not satisfy you. Just for beginners there is no way to tell for sure that the actual colors of a textile are those of a digital image (images vary from the actual, naturally, and some sellers manipulate colors shamelessly). And you cannot handle a piece you are considering on the internet at all.

I know one oriental rug dealer with 40 years of experience who will not buy on the internet because, as he says, “We make so many mistakes when we have them in our hands, why would we give any of that up?” And another frequent dealer on the internet will not finalize any sale or purchase until the buyer has the piece in hand and is still satisfied with the deal.

So unless you feel sufficiently knowledgeable and experienced with regard to rugs and other textiles to deal with the uncertainties of intenet auctions and purchases, it might be best to avoid them.

Bob mentioned that one real advantage to shopping on the internet, and eBay in particular, is that you can sometimes find interesting rugs and textiles in places where you would never consider shopping for them. To illustrate this Bob gave the seller’s location for each of the items he brought to show, even though this last step of the provenance chain usually tells us nothing useful about the item itself.

Despite uncertainties noted above, quite a few people DO explore both eBay and the internet more broadly, looking for textile opportunities and bargains. And some, sometimes, do well. Bob seems to be one of these.

A first consideration when buying rugs and textiles, on eBay especially, is the size of the universe of things being offered.

Bob said that when he first discovered eBay in the late 1990s and began to look at the listings of oriental rugs, there might be a few hundred pieces for sale, a universe that one could afford to look through.

But then, he said, within a year or two, many dealers posted huge numbers of rugs and there were, for a time, literally thousands of rugs (at one point around 25,000), most of which were just in the way of finding something of interest. During this period, one had to be clever with key word searches, both to cut the universe down to something managable, and to surface particular types of interest.

More recently, Bob reported, eBay has divided its rug and textile auctions using some helpful categories.

There is, for example, a “Pre-1900” category and as I write there are today 235 rugs on auction under this label. This does not mean that all of the rugs so labeled were in fact woven before 1900 (even being as honest as we could be, estimating age accurately is one of the things that we do least well), but it does provide a managable universe to examine. The flip side of this is that there are undoubtedly pre-1900 rugs, some of which might be desirable, that are listed in other age categories, or that the seller did not put in any age category at all; many sellers simply don’t have enough knowledge of rugs to be able to identify them to type or age, and consequently just list them in a more general category.

One could also first search “Antiques” and then, under that result, “Rugs and carpets.” Again, as I write, there are 511 on-going auctions that fit this description. This is also not an impossibly-sized group to examine.

And one can attempt custom searches of various sorts. For example, words like “torba,” or “chuval” or “yastik,” will yield pretty small groups, if these terms reflect your interest.

Various strategies of search can be designed and tested for results. Once, looking for folks who might have antique Turkmen rugs that they didn’t know much about, I did a search on eBay for “Bokhara.” I used all of the spellings I could think of.

Such a search COULD produce a large number of low quality rugs for inspection, but in the case of my own search I found and bought at a bargain price, an unusual 19th century Yomut main carpet with a white ground border and a well-articulated “tauk naska” gul.

But I took a huge chance in bidding on this rug. Neither the person who put it up on eBay or the actual owners knew anything further about it and while the colors looked good on my screen, I literally, threw $X,XXX out into cyberspace and then sweated blood hoping against hope that there were no synthetic dyes in it. I lucked out, but it could have turned out very differently. It was, at bottom, a foolish thing to do.

Sniping:

Perhaps most readers will be familiar with the internet auction practice of “sniping,” but I’ll approximate Bob’s description of it. “Sniping” arose as the result of a particular dynamic of internet auctions.

When a textile (or anything) is put up for auction on eBay, there will be an indication of whether there is a “reserve price” (an unstated lowest price the seller will accept) and a date and precise time at which the auction will end. Sometimes there will be a few low bids early in the auction period, but then there may be days during which there are no bids. What is happening is that most interested bidders are waiting to bid at the last moment to avoid driving the price up. This effort to bid at the very last minute is “sniping.”

A great deal of sniping is done individually by bidders and some bidders are adept at putting in bids successfully as late as one minute before auction end. But sniping is a task that software applications can do better than human beings and so hundreds of “sniping” programs have been developed and are on sale on the internet. A sniping program might claim to be able to make a bid for you in the last 5-10 seconds of an auction. So you sign up for a given sniping program and pay a fee for it to bid for you at the very last seconds of an auction.

Here, FYI, are the results of a Google search I did as I write on “free sniping programs”

http://www.google.com/search?hl=en&q=sniping+software+free&btnG=Search

Bob Emry said that he used some sniping programs, so I asked him whether he could recommend some. He replied:

“…Regarding sniping programs, there must be hundreds available and I’ve had experience with only a couple, so not much basis for recommending.

“However, it could be pointed out that, depending on your anticipated amount of eBay activity there could be sniping programs that are more advantageous for you.

“For example, some charge a flat-rate per month–say $5.00/month. This is okay if you are buying lots of stuff. But there are other sniping programs that charge a percentage–one I have used has a fee of 1% of bid amount of each successful buy.

“So for purchases under $500 per month, the latter would be more economical, and over $500 per month the former would be better.”

Bob also mentioned some other internet sources for rugs and textiles. He mentioned in particular Rugrabbit.com, a site populated by many of the dealers that collectors patronize. Rugrabbit.com is also a convenient, inexpensive place to sell a collectible rug or textile on the internet. Here is the link:

As I write there are over 7,000 pieces offered on Rugrabbit.com, but it is easier to examine offerings of potential interest than this number would suggest.

Many dealers in collectible rugs and textiles also have web sites. One ready listing of such sites can be found in the “Links” sector of Turkotek.com, the rug discussion board. Here is the link to this sector:

http://www.turkotek.com/links/links.htm

You are now equipped with more internet rug and textile resources than you can likely use in a life-time.

After these comments on buying rugs and textiles on eBay and other internet sources, Bob moved to treat the pieces he had brought, about three for each year from 1998 through 2008.

As I mentioned, all of his pieces had been bought on eBay. He noted that since the eBay source is the only organizing theme for his presentation, a more succinct title could have been just “potpourri,” and he brought rugs, bags, bands, trappings, and even “second-hand clothing.”

Bob organized his pieces by year bought, beginning with those bought first, in 1998, and ending with a piece that had come in the week of his presentation. He makes it his practice to print off the eBay page on any piece on which he is the winning bidder, so he was able to say in each case both when he had bought it and the geographic location of the seller.

Bob said that the complete khorjin set below is the first piece that he bought on eBay.

It is Luri from south Persia. Here is a closer look.

And this is what its back looks like.

Bob estimates that this piece was woven late in the 19th century. It came to him from Ontario, Canada.

The next piece was the Chinese rug below with a central dragon. Bob believe this is likely a section of what was originally a much larger rug; the warps actually parallel the long dimension (horizontal as shown here), and the long edges have no original selvages, presumably having been cut.

Bob described this rug as likely of the Ningsia variety and sees it as 19th century. He said that he quite likes this dragon.

Some seeming corrosive dye usages (not cutting) have created interesting beveled effects.

This rug came from Lawrence, Kansas.

A second Chinese piece was the one below.

This is a type of wagireh or sampler, intended to provide potential customers for a given line of Chinese rugs with “in the wool” examples of 50 available colors.

Bob estimated this piece to the 1920s. It came to him from Hadley, Massachusetts.

The fourth rug was the eastern Caucasus piece below.

The “Saint Andrew’s cross” field design and the Seichur-type border are characteristic.

19th century with a good range of color. It came to Bob from El Paso, Texas.

The next piece was a side panel of a small, flat-woven mafrash.

Bob described it as Kurdish. The weave is a brocade. The closer look below shows its superb colors more accurately. The wool quality is also exceptional.

Bob bought it from a dealer in The Netherlands.

The sixth piece was the Caucasian horse cover below.

Bob estimates that it came from the Karabagh area, and probably Azeri weaver.

Lots of color and fantastic animal designs. It came to Bob from Oregon.

Next was another complete khorjin set, this time from NW Persia or southeast Anatolia.

This piece is worth examining, but hard to photograph satisfactorily.

First, in a closer look at one pile face, notice the wonderful darker green ground of the main border.

But a really unusual and puzzling feature is the structure of the connecting bridge between its two halves. It is woven using “weftless sumak.”

“Weftless sumak” is a structure composed entirely of warps and the wrapping wefts that provide the colors and the designs. There are no structural wefts between rows of wrapping, as is the case with most sumak. The puzzling part is that this weftless structure is not very strong and so is ill-suited to perform the stressful functions assigned to a khorjin bridge.

There are some who feel that “weftless sumak” is a technique used only by Kurdish weavers, and if so, its presence is diagnostic of such an attribution.

A further odd result of this lack of ground wefts is that this bridge lacks the “interlacing” seen by folks like Marla Mallett to be an essential requirement before we can call a structure an instance of weaving. So, technically, this bridge is not just structurally weak, but outside the category of “woven” textiles.

This unusual piece came to Bob from a small town in western Idaho.

The eighth rug was Baluch or Timuri below. Bob estimated that is was woven in the Mashed area of Northeast Iran.

It has a complex field with interesting white highlights.

And it has a white-ground, graphically strong main border, clearly borrowed from Turkmen usages. Bob called attention to the unusual blue meander minor borders.

This rug came from Portland, Oregon.

The next piece was a flatwoven salt bag. It is Kurdish and its face is done using an extra-weft float technique.

Its shape is a little unusual, since its neck is not much narrower than its body. Here, also, is a look at the the dramatic zigzag design on its back.

It came to Bob from Connecticut.

The next piece was a side panel from a Shahsavan cargo bag. It came to Bob from Chicago.

This piece is unusual and more desirable to some Shahsavan collectors because it has borders on all sides of its field (many such panels have borders at the top and bottom only).

There is a great deal going on in this piece and the strong borders could be seen to diminish the effect of its field. Here is a corner close-up of these rich, graphically powerful border systems.

And below is an isolated detail of one of the field devices to let you better appreciate the qualities present in the field.

The next piece was a Turkmen chyrpy.

Most will know that the sleeves are false and that these silk embroidered garments were worn draped from the head. Chyrpys are frequently lined with commercial Russian cottons. Below is a detail of such a fabric used to line this one.

This chyrpy was auctioned from Honululu.

The next item was the Caucasian salt bag below.

Effective graphics. Bob described it as likely woven by Azeris. It came to him from Belmont, Massachusetts.

Textile 13 was a child’s hat.

Bob suspects that some parts of the hat are older–the fine cross-stitch embroidery of the upper part, above the row of red and green beads, for example–and that some of the ornaments might have been added later. Look closely and you might see that the rows of silver-colored beads are really many key chains, complete with the connecting clips that here link the sections together.

To repeat, the material that makes up the crown (omitting the top decorations) seems older.

Bob said this hat was made in east Afghanistan and came to him from Chatanooga, Tennessee.

A next piece was the Caucasian rug below.

Bob attributed this piece to the eastern Caucasus, and the color suggests Seichor area. He said that this is one of very few pieces that he has had repaired–in this case one of the ends has been rewoven, and some of the corroded black outlining replaced. It came to him from Boston.

The next piece was a Yomut asmalyk. This has the design that is most commonly seen in Yomut Turkmen asmalyks, but this one has uncommonly good quality and condition.

A closer look at a detail of a lower corner of this piece.

And a close detail of one field ornament.

Range of color is pretty good for a Turkmen piece. Numerous small elements, especially in the striped lattice, have what Bob interprets as an insect dye, cochineal probably, and the pile wool used for these small elements is 5-ply, rather than the 2-ply wool used for the remainder of the pile.

Bob said this piece came from Bakersfield, California.

Bob’s next piece was a rare-ish Turkmen format. Bob identifies this as a germech, probably Ersari.

The germech is a torba-shaped rug said to have been hung (perhaps on a rod) at the lower part of a Turkmen tent door below the engsi. Folks entering the tent would have to step over it, but presumably it would keep the “chickens” out. Writing in the early 70s, Azadi said that he knew of only four pieces of this format at that time. He said that their field device(s) are all taken from engsi elems.

Some have suggested that the presence of the distinctive “double-ramshorn” border found on most engsis is also diagnostic of this format. This example appears to meet both of these criteria.

I wonder whether the person in Toledo, Ohio who sold this piece to Bob in an eBay auction knew something of the rarity of the piece he had.

The next rug was the Balouch piece below.

Here is a closer detail of a corner.

Here is a closer detail of a corner.

And here is a close detail of the field. It has dozens of small highlights in magenta silk.

Here is an even closer detail, to let you enjoy these silk highlights.

This colorful, graphic piece came to Bob from Dusseldorf, Germany.

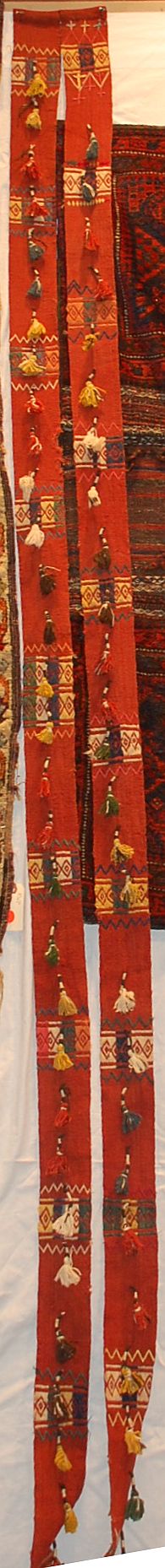

The next piece was the pack band below. It is about 16 feet long and three inches wide. It is warp-faced, with the design in warp substitution. Near each end the warps are divided into two groups and plaited into two bands, which come together again at the very end are formed into a dense ball.

Here is a closer detail of it.

This warp-faced band came from Iowa City, Iowa.

The piece below is a Southwest Persian bag.

This piece is attributed to the Luri. Here is a closer look at its strikingly different back.

Bob bought this piece from someone in Bristol, England.

The next piece was the Jaff Kurd bag below, with a darker color palette.

Here is a closer upper corner.

This piece has a number on its back stenciled with white paint.

Such numbers are often found on pieces from The Netherlands, so it is not surprising, once we see them, to find that that is where the person from whom Bob bought this piece was located.

These numbers were once the focus of a discussion on Turkotek.com. A Dutch dealer who was interested began to investigate these numbers and the reason(s) why they were applied. He found that it was a system used by an importer in The Netherlands during the 1930s and, Bob remembered that the numbers found always seemed to be odd ones, and that made folks wonder why there were not even numbers. Oddly, and rather ominously someone said to the Dutch dealer, who was asking questions about these numbers, that he should stop doing so. I don’t think that got solved. 🙂

Bob next showed the Yomut torba below.

Bob said that, in his view, this piece was woven by a very skilled weaver; it is finely woven and very regular, without a single knot out of place. Here are some closer details of it. First, a strip to show off its borders.

And below is a close-up of one field device.

This nice piece came to Bob from Massachusetts.

The next piece was a fragment of a Uzbek suzani.

As you can see this fragment is composed of three small border fragments. Bob estimates it to have been made before 1850. Below is a detail of one of its colorful embroideried flower forms.

This piece came to Bob from The Netherlands.

The next piece was the Uzbek band below.

Bob described this as a “decorative” band, contrasting it with those of more functional purposes. Here is a closer detail.

This band came from Iowa City, Iowa.

The next piece was a narrow Tekke Turkmen rug that was shown in the TM’s Symposium show and tell, and featured in my most recent post. Bob included it in his “rug morning” program because it was bought on eBay.

In my treatment of this piece in the “Symposium show and tell” post, I said that I thought that I had heard Jon Thompson suggest that it might have been a kind of engsi, a door rug that hung inside the tent door. Acccording to Bob, who remembers more of the details of Thompson’s discussion, Thompson said that, in his discussion of a piece with similar format in the Sotheby’s catalog for his sale in 1993, he had mentioned that someone had suggested that these long narrow pieces were suspended by the two ends, inside the tent door, to make a U-shaped shelf for a hat. But Thompson continued that he does not regard this hypothesis as very likely, and thinks it more likely that these were made to serve some kind of special ceremonial function.

Here is a closer look at some of the guls in its field that show the use of silk in their internal instrumentation, something that would seem to suggest a special occasion piece.

This unusual rug came to Bob from Toledo, Oregon.

The next piece was another Jaff Kurd bag with a darker palette.

Here is a closer detail.

Jaff Kurd bags can seem ubiquitous, but a visiting expert on Kurdish weaving called this one a “world class” piece.

Next was the longish Kurdish rug below from NW Persia.

Bob said that even though this rug is “cut” and “pieced,” he was attracted to it because it appeared to have fantastic wool and superb colors, including a wonderful purple. Here is a closer look at one corner that shows its colors well.

A detail of its field shows the instrumentation of its red-ground medallion and some abstracted “shrub” devices, as well as the line on which it was cut.

A closer border detail that, again, shows its colors better.

This rug came to Bob from Salzberg, Austria.

Next was another complete khorjin set. It is Timuri, and Bob see it as a close analogy to Plate 56 of Baluchi Woven Treasures by Boucher.

Here is a closer look at one face and its closure system area.

The eBay seller from whom Bob acquired this piece was located in Germany.

The next piece was the Chinese seat back below.

This rug feels like an older piece. Bob described it as Ningsia and believes it was woven about 1800 or even earlier.

It came to him from Richmond, Virginia.

The next piece was another unusual Turkmen format.

Pieces with this shape are called “salanchaks” (sometimes “salatchaks”) and are often said to be a species of cradle (some have what seem like suspension cords). But this piece is considerably larger than some other salanchaks and it has a niche design, permitting speculation that it could have a prayer function. Some also see such pieces as possible saddle covers of the sort that go under the saddle. And still others have suggested that such a rug might have served as a funeral rug, placed on or under the corpse during the funeral observances, and then retained for other subsequent uses.

Back in the earliest days of Turkotek, Wendel Swan fashioned a salon on a striking flatwoven salanchak he had encountered (I think) in Canada. The image of it and Wendel’s initial salon essay have been lost in cyberspace, but if you are interested, some images of similar pieces, parts of the interesting salon discussion, and Wendel’s end-of-salon summary, are available at the following links:

http://turkotek.com/salon_00002/messages/74.html

http://turkotek.com/salon_00002/messages/86.html

http://turkotek.com/salon_00002/messages/87.html

http://turkotek.com/salon_00002/messages/89.html

Here are some closer looks at this Yomut piece. First, its lower left corner.

The designs clearly signal a Yomut attribution. Here is the upper left corner.

Notice that this piece is inscribed.

Bob noted that the first three characters of this inscription appear to be 122, which might suggest a date, if the fourth character is also a number. Islamic years beginning with 122 would be between 1805 and 1814, almost certainly predating the rug, but possibly not too old to be the birthday of someone the rug was made to commemorate, perhaps as a funeral rug. Bob said he has not been able to determine what the rest of the inscription says. He noted that inscriptions in Turkmen rugs are, as a rule, extremely rare; however, among salanchaks the incidence of inscriptions is actually relatively high, which might support the idea that they were made as some kind of commemorative pieces.

It came to him from Birmingham, Michigan.

We moved next to the Anatolian rug below.

Here are some closer details of this piece that combine a niche treatment with a central field medallion. First, the medallion.

Then, the upper right corner with a glimpse of the niche and a better look at the border systems. There are some areas of advanced wear, but where the pile is good the wool is very soft and silky.

Bob believes this piece was woven in central Anatolia, but might come from farther west. It came to him from Amsterdam.

The next piece was the Turkman chuval below.

This piece would likely be called “Middle Amu Dyra” by most now, but it has the “stacked” gul and marks within the quarters of the major gul usages sometimes associated with Kizil Ayaks. The minor gul is even more spacious than the major gul, and Bob said he had been unable to find another piece with this particular minor gul.

It also features a liberal use of an unusual light green, a nice brighter blue and a clear yellow.

Notice also the unusual zigzag outer side borders.

Here, below, are some additional details that show the colors in this piece better.

The owner who sold this piece to Bob was located in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Bob’s next piece was a Turkmen main carpet with “tauk naska” guls. He believes this piece to be a 19th century Kizil Ayak.

This rug has several unusual features. Notice that the main border on the left differs from that on the right. Perhaps the most unusual feature of this piece is that in nearly all the “animal” figures, in the quarters of its major guls, the two heads face in opposite directions.

The more usual drawing has them facing the same way, which is seen in just a few instances in this rug, all of them in the lowest row of guls (first to be woven).

Bob said that he knows of only one or two other rugs in which the heads of the tauk naska devices face in opposite directions.

This rug came to Bob from Honolulu.

This next piece was a complete flatwoven khorjin set.

Here is a closer detail of its designs and colors.

This colorful piece was attributed to the Shahsavan.

It came to Bob from Germany.

Bob’s penultimate piece was the classic “Beshiri” prayer rug below.

Although the “Beshiri” designation has shifted nowadays, it is used here because it is the most familiar one used to describe a piece of this type, until recently, in the literature. Such rugs seem likely urban and may be better seen as among the sort that Jon Thompson described with the term “Bokhara” in his 1980 “Turkmen” catalog.

Here is a closer look at the central, niched field of this piece.

And here is a close look at its border system.

This rug has some wear, but is still a very desirable instance of a classical type.

Bob said it came to him by indirection and chance from Carlsbad, California. It was up on eBay, and he had bid, but the seller took it down before the end of the auction, something that usually signals that the seller has made a favorable deal on the side.

Bob said he wrote the dealer, saying he was disappointed that the auction had been canceled, and signaled his continuing interest in this piece. Months later, to Bob’s surprise, the seller contacted him and offered it to him. Apparently, his “favorable deal” broke down in some way. Bob’s action here is something to remember. You might still get a piece you seem to have missed, if you express specific interest to the seller.

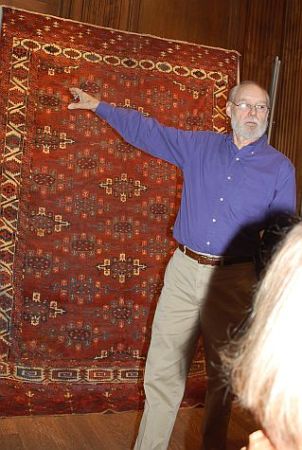

The last rug that Bob showed was the Yomut main carpet below.

Notice that green-blue ground kepse guls occur, moving in an upward diagonal left to right, in every other row. The kepse guls in the alternate diagonal rows vary in ground color between a lighter blue and a darker blue with white. In kepse gul carpets with this color arrangement, the guls with white are most often arranged in a pattern that reads a 1-2-1-2… as one moves up or down the rug. Carpets with this design all appear to be among the older group of Yomut kepse gul rugs. Bob believes this rug is early 19th century, possibly even pre-1800. In virtually all late 19th century Yomut main carpets with kepse guls, the diagonal use of color varies regularly row by row, with each diagonal row having guls only of one color.

Here are closer looks at this rug.

The “elem” designs at each end are different and Bob indicated that the one at the top of this rug, shown in the upper corner image above, is more unusual in his experience.

The detail of the field below shows the articulation of the drawing of the kepse guls.

Bob said that this is his most recent eBay purchase and came to him the week of his presentation from Wappingers Falls, New York..

Some in the audience had brought in pieces bought either on eBay or from some other internet location. I do not have notes on them, but will indicate what I can recall.

The first piece was this Balouch rug with a niche design.

Although Craycraft suggests that the lack of white may indicate greater age, this seems a less than old version of a “doktor-e-ghazi” design.

Here is a closer detail.

The niche shape follows the traditional “doktor-e-ghazi” usage.

The next piece was an initially vague-looking flatweave.

A closer look revealed considerable color and detailed drawing.

Next were two Anatolian yastiks, both bought on eBay.

The owner said he bought the piece below primarily because of its unusual purple ground.

He believes that the orange that attracts the eye is natural.

His second eBay piece is one with which some of us are familiar.

This piece is very well composed, has good colors, and an interesting and brightening use of white dots over much of its area.

This piece has been published, most recently by Ralph Kaffel, in an article on unusual Anatolian pieces in Hali 157, indicating that it is possible to find and buy weavings on eBay and the internet that rug scholars might find worthy of notice.

The owner of the piece below offered it as an example of how difficult it is to estimate colors accurately from digital images on the internet.

This Shahsavan piece is very well drawn, has a nice, framing border all round and is extremely well woven…a tough, tough fabric. But, its owner said, its colors in the wool are not nearly what he thought they might be from what he saw on his monitor.

The next piece was the Anatolian niche design rug below.

Its owner has subsequently shared with me how the dealer from whom he bought it on eBay in 2000 described it before purchase.

“Here is a Konya prayer dating to the late 19th century, measuring 3’4″ X 4’9”. Konya is the ancient Iconium, one of the great ancient cities of Asia Minor. The wool from the region is world renowned and this weaving has the very best wool in it. The peoples of the Konya region were largely Turkoman people 500 years ago and weaving has been carried on here for many centuries. The dyes in this wonderful little prayer rug are eye popping. In fact the colors are so arrayed that they define depths of varying intensity.

This is a flawless and important Anatolian prayer rug. The rug has visual depth by virtue of the power of its’ color alone.

I mean to tell you the sky blue in the upper field you are seeing isn’t created with computer processing, that is the real color!!! The black background of the border is a corrosive black and creates an embossed effect for the wonderfully colored floral bouquets. In the center of a very few border elements are little groups of 2 or 4 knots of synthetic orange, maybe 20 knots in all.

Weavings from the 1880’s often show this tentative use of the new synthetic dyes so I date this weaving to circa 1885-1890. All the colors in this rug could be used as examples of the finest vegetable dyes in the world. This rug well lit on a wall sizzles with color intensity like stained glass. This is a major collector’s piece and could highlight almost anybody’s collection. The weave is very soft and floppy at 60 KSI. In the end here one is considering a major artwork in this weaving and something of enduring value.”

This description is provided to let you see how some dealers describe pieces they are offering. How could we resist, right?

This same owner brought a second piece, also on eBay, from a different dealer. This piece is the Uzbek, velvet ikat fragment below.

Again the owner has provided the dealer’s description of this piece as it was being auctioned:

“This listing is for an exceptional Antique UZBEK SILK VELVET IKAT POUCH from the 2nd half of the 19th century. A powerful and visually striking storage bag for the yurt probably used to secure precious items for the owner. It is a patchwork composition of Baghmal (silk velvet ikat) pieces including the inside of the bag. This piece is in pristine condition and has a lovely Russian trade cloth backing framed by silk ikat strips. This is one of those rare textile artifacts that collectors covet and hold in the highest esteem. It is simply a wonderful treat just to handle this extraordinary weaving. Fresh to eBay viewers from the other side of the globe. Size: 14″x16″.”

These two quotes should give you a sense of how some dealers, offering textiles for sale on the internet, describe them.

The next “brought in” piece was a complete flatwoven mafrash.

Strong graphics and good colors make this an attractive piece. Here is a closer detail.

It was seen as mostly likely woven in the Caucasus, but also possibly in NW Persia.

The next piece was the child’s dress below.

The image above is of its back. Here, below, is one of the front.

And here is a closer detail of one vent.

I think its owner said that it came to him from Tiblisi, Georgia. It attracted the attention of some experienced collectors in the room.

The next piece was a fragmented Turkmen chuval.

Its owner said that it was sold to him via the internet as a “late Saryk” piece. Thompson does talk about later Saryks with a darker palette and asymmetric open right, rather than symmetric, knotting. So that was a fair description of this piece at purchase (today it would more likely be seen as Middle Amu Dyra).

Its major guls have the cruciform center of many Saryk pieces and the elem is interesting if not necessarily diagnostic.

Its owner said that he had brought in this piece as an example of how different colors seen on one’s monitor can be from what one encounters “in the wool.” (If you see signs of dog hair in this close-up, it is because his wife’s champion collie sleeps on this chuval.)

This piece is MUCH darker in hand than even the unmanipulated digital images above suggest, but, the owner said, what he was looking at on his screen at purchase was so different from what arrived, that the piece was nearly unrecognizable. He subsequently discovered that the dealer from who he bought it is famous for manipulating the colors of the digital images of the textiles he offers for sale.

The next piece was a Persian pictorial rug from Firdowz, in Khorasan.

It was bought via the internet, but not on eBay. Its owner said that he first saw it, with a number of others, posted on “Rugfanatics,” a discussion board. A lady in The Netherlands put up a number of rugs in her collection for comment.

The current owner said that while he doesn’t usually like pictorial rugs, he liked the “blocky” figures in this one and wrote the lady on the side and ultimately bought it, despite a momentary misunderstanding about whether the stated price was in US dollars or euros (this was when the U.S. dollar/euro exchange rate was much closer).

Although it is clear that this rug has no great age (among other things its warps may be hemp), its current owner said he fantisized, initially, that perhaps its blocky figures were based on some ancient Luri sculptures. Unfortunately, Tanavoli indicates that these figures are more likely based on those in Russian icons (although the episodes illustrated ARE from the Persian folk tales about the star-crossed lovers, Khusraw and Shirin) and the owner of this piece now knows of two “Mary and Jesus” rugs with these same type human figures.

This rug is an example of the rather convoluted way in which one can encounter and acquire a rug on the internet.

The next rug was the large pile rug fragment below with a compartmented design.

The owner said that he bought it on the internet after a friend attracted his attention to it. It is Turkmen, has an asymmetic open right knot and would likely be best called Middle Amu Dyra now. He said that he knows of only three examples of this design and believes that that this piece could have significant age (notice the narrow border, often seen to indicate an older Turkmen piece). One other noticeble feature is that this piece has bright orange wefts.

The owner also reported that this piece has been professionally washed since he owned it and the washer reported that some red dye and a yellow came out in that washing (the piece was purchased mounted on its current tan backing, and there was some transfer of red to this backing as a result of the washing). The owner still thinks that this is likely an older piece, but cannot explain the seeming behavior of these dyes if all of them are natural.

The next piece was an Anatolian yastik that the owner reported attempting to buy on eBay.

But he said someone else won the eBay auction. As a result he had to pursue this piece by internet to Germany and pay more for it, including the additional shipping.

It is an example that demonstrates that unsuccessful sniping can be expensive.

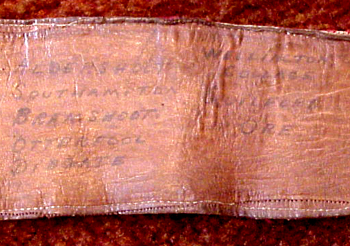

The next piece was very unusual.

The owner said that he had bought it by nearly sheer chance on eBay. It is a needlepoint-faced leather belt, apparently made during one of the world wars for a soldier. The owner said that he had previously encountered one other example of this type in an antique store in Medina, Ohio. Here, below, is an image of this Medina example.

This second one has a British Union Jack flag design and a date, perhaps 1919 (suggesting something of a WWI era). Notice the nice detail of the simple border.

The basic character of these two belts is identical. They both have brightly colored needlepoint fronts and leather backs with a pocket.

Both have the same two-buckle system and the designs are often of flags, flag-like panels, shield devices (as in this one), and initials. It may be that they are the product of a kind of kit sold during the war(s).

One further interesting addition to this one is that a series of words are written on its leather back in ink.

There are at least 23 names inked onto the leather back of this belt in a little more than four columns.

It turns out that these are all names of British military bases.

A very odd textile, likely not to everyone’s taste, but the owner is quite taken with it. He would own both of them, but the asking price on the Medina piece was prohibitive.

The next rug was another brought in as a cautionary example.

This is a fragmented rug, likely of respectable age, but in very poor condition. The owner said that he collects on a rather severe budget, and so will buy things that most others would pass by without a second look.

This rug was bought from Germany on the internet, but not in an eBay auction.

The dealer had some interesting observations about it. He said that it was likely woven in the Middle Amu Dyra area, but that he suspected that he could attribute it more accurately than that.

He said that the knots were very “thin” (he may have meant that the cords with which they were made were of a small diameter, perhaps also pounded down tightly) and that as a result the tied knots were noticably “short” on a vertical axis. He said that the Salors made “thin” knots of this sort, but that this piece lacked any other Salor indicators. He said that the only other tribe that wove such “thin” knots were the Arabatchis. Since, there were Arabatchis in parts of the M.A.D. he felt it most likely that this piece was woven by Arabatchis from that area.

As you can see in the image above, this rug is in poor condition, but the selling dealer also said some things that a discerning reader would have seen as signaling that there were further problems with this piece. BUT he never actually mentioned “glue,” and it was only when the current owner of this piece had it in hand that he saw that the additional problems included the fact that someone had used glue on parts of the back to attach it firmly to a floor.

This feature presses this purchase firmly into the category of a “study piece (the owner may sometime experiment with something called “Zip Strip,” a kind of paint remover used by some rug folks to remove some types of glue from a rug surface). It also demonstrates, dramatically, the advantage of reading carefully everything a dealer says about condition.

The last “brought in” piece was this flatwoven item.

Here is a closer detail.

The owner of this piece has, subsequently give me the description below:

“…I bought it on ebay in 1998. it came with an incredible note saying that is was owned by a curator at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum.

“Attribution: Probably Afshar weaving from N.W. Persia, South Caucasus, Karabagh, Transcaucasia. Also, possibly a Shahsavan or Azeri weaving . This can be called a ‘verneh,’ but Tanavoli and the Vok collection have one similar that they call a ‘masnad’ which is a type of verneh.

“Fantastic natural dyes of many colors on hand spun cotton. late 19th century…”

I want to thank Bob for permitting me to share a virtual version of his interesting “rug morning” program with you. And to both Bob, and the owner of this last rug above, for their editorial assistance. My thanks, too, to a nice lady who chanced to sit beside me, and who took a legible, useful set of notes, but would not permit me to thank her here by name.

I hope you have enjoyed another virtual version of one of The Textile Museum’s very interesting and informative RTAM programs.

Regards,

R. John Howe

You must be logged in to post a comment.