On August 24, 2013, Steve Price

gave a Rug and Textile Appreciation Morning program on the subject “Traditional Clothing from Southeast Asian and Africa.”

Steve Price was, until recently, a professor of physiology at Virginia Commonwealth University. But he has also been active for a long-time in the rug and textile world. Currently, he is the most prominent owner-manager and the leading technical director of a non-commerical discussion board called “Turkotek.” http://www.turkotek.com/ Steve has written for Hali and the Oriental Rug Review and has given lectures and presentations in a variety of settings, including a number of previous RTAM’s programs. He is a recognized figure in the world of rugs and textiles.

Steve began by saying that since he is a professor he must, unavoidably, do some professing, but that he would keep it to a minimum, since he knows that most folks come for the material.

I took no notes in this session and so have imposed on Steve to rehearse for you his initial comments and then to describe and comment on the pieces he brought. I brought four pieces, some of which may be off topic, but about which they have graciously permitted me to speak to at the end.

(Note: If you click on images most will appear in a larger version. That will be useful in some of the closer images provided.)

The bulk of the commentary will be Steve’s and that will start now.

I began by saying a few words about why clothing even exists. One reason is obvious enough, it’s protection from the elements and other elements in the environment like thorns, ticks, etc. But it also serves other functions.

1. It announces our identity and place in society. We don’t need to see the pope’s face to know who and what he is. The bride and groom are usually easy to identify at a wedding, just by the way they’re dressed. Likewise for a police officer, a judge, a firefighter, a nurse, etc.

2. It provides modesty, covering parts of our body that custom or religion demand not to be exposed. This is quite different in different social and religious groups, and tells us a bit about what modesty means in each of them.

3. Some clothing is believed by the wearer to have supernatural powers that protect against assorted forces or invoke special abilities.

4. It adorns and beautifies the wearer. This will be our little secret. The community of textile collectors (especially rug collectors) are offended by the notion that many textiles are beautiful simply because the weaver liked to make beautiful things.

A1

That’s me, struggling to find the right head and arms openings for a Nigerian men’s garment referred to in the trade as a “grand boubou”. I have no idea whether it’s called that in Nigeria, but it has a nice ring to it. It’s woven of narrow strips sewn together to form the garment, then embroidered. They’re usually done in the indigo palette of this one, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen one in which the indigo hasn’t stained the embroidery (which starts out white in most, maybe all). The embroidery patterns are quite traditional, and have names. I don’t recall the names of those on this garment. The wearer’s costume would also include baggy trousers that match the boubou; my blue jeans are a poor approximation.

Here I am, emerged from my cotton prison and obviously relieved to be back in the light.

Detail images of A1:

The next piece is the first of a few examples of west African strip-woven cloths refereed to in the west as Kente. I believe that term was originated by the British. The narrow strips are sewn together to form the whole piece. The blocks of decoration are done in supplementary wefts, and are referred to as motifs. Every motif has a name and is associated with some little story or saying. This piece has only a few motifs, repeated throughout the textile. The patterns on the ground cloth also have names and signify characteristics with which the wearer would like to be identified.

Kente cloths are garments, wrapped around the body with one end thrown over a shoulder. This one was done by the Ashante, and its dimensions are those of a woman’s garment.

A2

The next piece is another Kente cloth, also probably a woman’s garment. It’s a product of the Ewe, neighbors of the Ashante people. A distinguishing characteristic of Ewe cloths is that the motifs are absent in what amounts to a border. This one has a somewhat wider assortment of motifs than the first piece did.

A3

The next piece, another men’s Kente, is the best of the three. The ground cloth pattern signifies that the owner was a man of some importance, perhaps a village chieftain, and there’s a large number of different motifs. The ground cloth is a mixture of cotton and silk, the motifs are silk. According to the folks at the Museum of African Art on the Washington mall, it was woven in the town of Bonwire for somebody important, and cannot have been woven later than the 1930’s. The colors are wonderful.

A4

The next piece is a full length tunic (it’s about 5′ tall at the shoulders) made of strung glass beads sewn to a while cloth backing, with a strip-woven lining. It’s extremely heavy, and the TM volunteer who modeled it was a real soldier about the whole thing.

I’ve had it looked at by a number of experts, the consensus is that it’s probably Nigerian, perhaps a vestment for a priest, although none had seen anything quite like it (waist length beaded tunics are fairly common). There’s an interesting assortment of motifs, some with fairly obvious implications (could elephants represent anything except strength?), others not so obvious. Cowry shells, used around the opening for the head, usually symbolize wealth or fertility in African cultures.

I acquired this piece from a local dealer who was the wife of a now departed very good friend and colleague. It was covered with black, oily dirt, and she thought I might know how to clean it up. I bought it from her very inexpensively, brought it home, and it was promptly declared unwelcome indoors by my wife. I spread it out over some folding lawn chairs outside, scrubbed it with Spic ‘n Span for several days, and finally got it to its current state. It is a perfect cover for our standing rack that holds VSR tapes (don’t ask), and does well in the sun-soaked room in which we have it. No fading, unlike any textile.

A5

The next group of textiles are from mainland southeast Asia (Kampuchea and Laos). Textiles from Indonesia and other SE Asian islands are very popular with collectors, mainland weavings seem to have slipped through the cracks. I think they’re marvelously sophisticated, and am surprised that they’re not more widely appreciated.

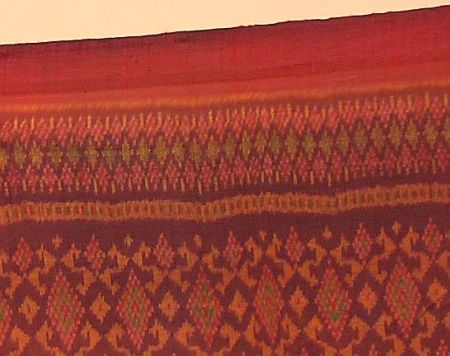

The first piece is a Khmer (Kampuchian) woman’s tube skirt. It’s all silk, very finely woven in a weft ikat technique. It’s worn by creating a single pleat-like fold to take up the extra width (it would probably fit a 40 inch waist otherwise, and Khmer women were petite),

SE1

Here’s another, same group probably about the same age (I don’t know how old it is, but I’m told that early 20th century is a reasonable guess).

SE2

SE3

The next one is the first of several hipwrappers, worn by men and women in royal courts.

Here’s another. These are probably 10-12 feet long. You’ll see how they were worn just a little further down the page.

SE4

Here’s our TM volunteer, recovered from the burden of the Nigerian beaded tunic, modeling a hipwrapper. It starts by being put around her, kind of like a horizontal sling.

Next, she holds the two sides together around her waist (I think a clip of some sort was used by the Khmer; she’s holding it closed with her hand.

I’m holding the ends of the sling, and twist them together to form sort of a rope. The rope then get’s passed through her legs and the end is tucked into the waist at the back.

As we noted above, this is a unisex garment. Yul Brynner wore one in his role as the King in “The King and I.”

The next group is also from mainland SE Asia, but these are products of Thai speaking tribespeople in the Laotian mountains (generally refereed to as T’ai tribes).

Their weaving uses more techniques than the Khmer court textiles; typically a combination of supplementary weft brocading, dovetail tapestry, and weft ikat. I only have one that includes ikat. Unfortunately, it’s mounted on a wooden stretcher that’s too big to fit in my car. You’ll just have to take me at my word when I say that the ikat work is as good as any I’ve seen.

The first few are skirts, silk except for the cotton replaceable panels at the top and bottom. They are said to be worn only at the funeral of the wearer’s mother-in-law, then passed down to the next generation. Is that true? Who knows. It’s obvious that they were for special occasions, though.

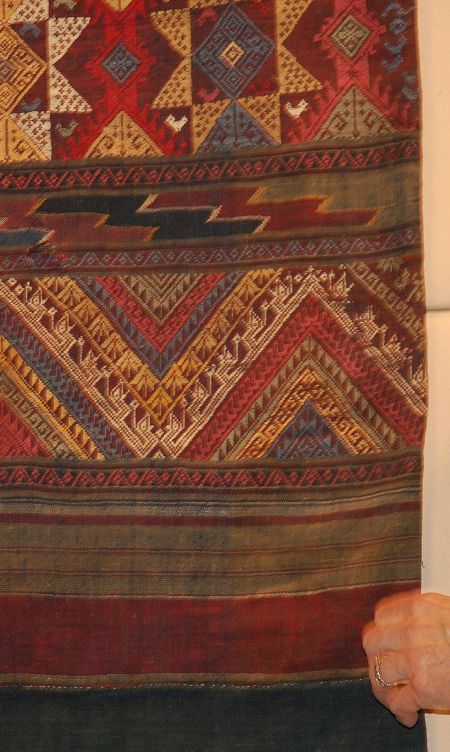

The first one has two tall bands of brocading sandwiched between shorter bands of tapestry. I think the colors speak for themselves. The white motifs in the lower brocaded bands represent serpents, and similar things can be seen at the edges of the roves of Thai temples. Serpents hold a special place in these cultures, connecting the underworld with the heavens.

SE5

The next piece is another skirt from the same T’ai tribe (my unreliable memory says it’s T’ai Hun, distinguished by the bands of tapestry). It has unusually elaborate tapestry work, reminiscent of Chinese “cloudbands”. You’ll also have little trouble finding a couple of kinds of birds and some floral motifs. The motifs in the uppermost brocaded band are remarkably similar to the eight-pointed stars that are so common in textiles throughout western Asia.

SE6

This is the third and last of the T’ai skirts. The serpent is depicted in the lower brocaded panel, some variety of bird in the upper brocaded panel.

SE7

This is my last T’ai piece, a shaman head or shoulder cloth of the T’ai Daeng. It’s very densely brocaded, with an assortment of motifs that fuse into other motifs (notice how the open mouth bird in the center can be resolved into two elephants) and lots of bits of color that are said to distract the evil eye. There are birds, animals, plants, even a few humans.

SE8

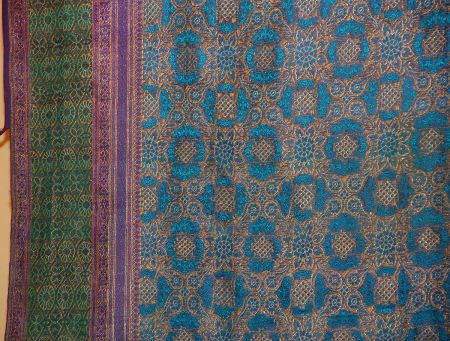

The last piece I brought was neither African nor southeast Asian It’s a sari from Varanasi (Benares), India, woven in silk and gold. It’s about 15′ long, and I rarely get an opportunity to display it because of its size. It has the remarkable property of changing colors as the viewing angle changes, which makes it great fun to look at when it’s waving about. This isn’t apparent in most of the photos; I’ll call attention to it in those in which it can be seen

SE9

Some areas transitioning from green to gold can be seen in the next photo.

(image below folded over to show back)

SE10

This is John Howe, again. As I said above, I brought four African pieces to support Steve’s program. The first of these (below) is an Ivory Coast, Dida, raffia, tube skirt, finger-woven and tie dyed. It is form-fitting and smooth on the inside despite the heavy texturing on the outside. It was woven by people of status on auspicious occasions.

BI1

I didn’t read the “clothing” indication and so the other three pieces I brought may be on topic, but one certainly is not.

The piece below is a substantial cotton, woven in strips and sewn together. I am not sure that it is an item of clothing, but it could be used as a shawl.

BI2

The dealer I bought it from initially said that it was from Togo, but when I pressed him indicated that he really didn’t know. I don’t know where in Africa it was woven, but west Africa seems to use a lot of blue.

The ivory strips are separate from the striped strips.

The next piece is just a mat and a familiar one. I brought because it illustrates that quite frequently encountered pieces can be an occasion for learning.

This is a Kuba mat.

BI3

The Textile Museum gave an exhibition of Kuba textiles in 2011-2012 and showed Kuba cloth ceremonial dance skirts (below is a detail of most of one such) and head-dresses, but my piece is just a small mat.

One side of such Kuba cloth has a velvety texture, while the back looks plain-woven, with the design showing only faintly, and the dark color on the front not showing at all.

But to return to the point about learning. I bought this piece because I like the side that has the dark areas and though I might fold it over to make a small pillow. On this side it looks like it is two pieces with a seam horizontally, BUT when you look at the back, you find that there is no seam on that side.

When I talked to an experienced person in this area, he said that all Kuba mats have this feature, with the front seeming to be of two halves and the back woven continuously. I am not sure of the significance of this feature, but it is Interesting.

The fourth African piece I brought in is clearly off topic. This flat-woven rug (very heavy) may provide clear evidence that I am not a discerning collector. The particular damning feature is that this piece is full of synthetic dyes.

BI4

It is in my collection because it was very inexpensive and is a known type woven in southwest Tunisia by Lybians who moved into that area at the turn of the 19th century with the development of phosphate mining in that area. More, it has a not unsophisticated design, that is completely and excellently executed.

The use of contrasting scale in the devices used is very effective. Even the color use, if one can forgive the dyes, is worth noting. The drawing of the detailed, internal instrumentation in the diamonds is well done. One brown-black wool was likely mordanted in iron and has fallen completely off in some places, leaving bare cotton warps.

Steve answered questions and brought his session to a close.

I want to thank Steve for this program and the considerable work he undertook to produce this virtual version. Nearly all of the text is his.

I hope you have enjoyed this look at some examples of traditional clothing from Africa and Southeast Asia.

Regards,

R. John Howe

You must be logged in to post a comment.